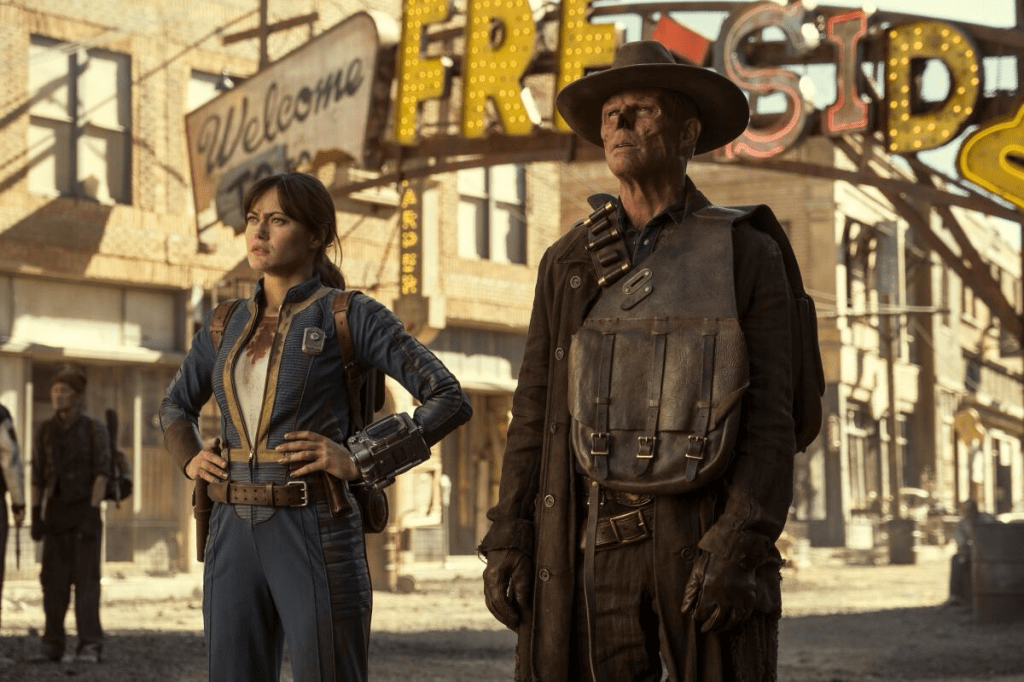

“Fighting the good fight is mostly a series of humiliations.” — Unknown congresswoman, Fallout, Season 2

I don’t know how many are watching Amazon Prime’s Fallout—call it a guilty pleasure—but one throwaway moment lands harder than most prestige television monologues. As an unnamed congresswoman is physically ejected from a New Vegas casino, stripped of status and relevance in a world that no longer honors either, she looks up at the show’s anti-hero and offers a line devoid of irony or self-pity: “Fighting the good fight is mostly a series of humiliations.” The moment passes quickly, almost unnoticed, but the truth it carries is enduring. In a collapsed world, moral action is no longer rewarded by institutions, nor even recognized by them. Dignity survives only in persistence.

The line sounds cynical until one recognizes it as a statement of structural realism. Across philosophy, organizational theory, and lived experience, the pattern is consistent: individuals who pursue truth, coherence, or moral clarity inside large institutions rarely encounter affirmation in real time. Instead, they encounter resistance, marginalization, and quiet forms of humiliation. This is not accidental. It is the predictable cost of remaining oriented toward reality within systems designed to preserve order.

The career and legacy of John Boyd exemplify this dynamic. Boyd’s ideas—on maneuver, adaptation, and decision-making under uncertainty—eventually reshaped modern military thought. Yet during his lifetime, he was frequently sidelined, denied advancement, and treated as a disruptive eccentric rather than a strategic asset. Boyd’s experience was not a personal failure or an institutional oversight. It was the natural outcome of an innovator colliding with bureaucratic logic.

From an existential perspective, Boyd’s experience aligns closely with Albert Camus. Camus rejected the idea that meaning is validated by success, recognition, or institutional approval. In an absurd world—one marked by uncertainty, contradiction, and moral ambiguity—dignity emerges not from victory but from persistence. To act rightly without assurance of reward is not a tragedy to be avoided; it is the condition of authentic action.

Boyd embodied this posture. He pursued clarity over comfort, coherence over consensus. He continued briefing, writing, and mentoring long after it became clear that institutional recognition would not follow. Like Camus’s rebel, Boyd said no—not as an act of negation, but as an act of moral orientation. His refusal was quiet, disciplined, and absolute: he would not accept doctrines that denied friction, designs that violated physics, or strategies that confused control with understanding.

Boyd Between the Rebel and the Bureaucracy

In the late 1970s, Boyd occupied an uncomfortable space familiar to both philosophy and organizational theory. He was neither an outsider seeking to overthrow the system nor a reformer safely nested within it. He was a rebel inside the institution—precisely the figure Camus understood as most threatening and most necessary.

Boyd’s rebellion was epistemic rather than political. He challenged foundational assumptions about air combat, decision-making, and organizational learning. In doing so, he exposed uncertainty that others worked hard to suppress. His briefings embarrassed programs, unsettled hierarchies, and punctured narratives of rational mastery. The response was predictable.

Here Max Weber provides the missing explanatory layer. Bureaucracies are optimized not for truth, but for predictability and legitimacy—no reason to be upset, it just is. They reduce uncertainty through rules, hierarchy, and procedural control. Individuals who surface ambiguity—especially at the level of first principles—are not engaged as equals. They are contained.

Boyd was contained through humiliation rather than expulsion. He remained in the system, but without command, without promotion commensurate to influence, and without institutional shelter. This was Weberian bureaucratic containment in practice: marginalization that preserves order while neutralizing disruption. Boyd’s reputation—brilliant but “difficult,” insightful but “unsafe”—was not accidental. It was the bureaucratic immune response.

The humiliation Boyd endured was cumulative, not episodic. Yet it served a paradoxical function. By denying him formal authority, the institution preserved itself. By denying him comfort, it preserved Boyd’s intellectual independence. His ideas moved anyway—laterally, informally, carried by students, reformers, and outsiders—long after the system had neutralized him personally. Only later were his concepts absorbed, often sanitized of their most unsettling implications.

Humiliation as the Signature of the Good Fight

Seen through this combined Boyd–Camus–Weber lens, humiliation is no longer a failure mode. It is a structural indicator. Existentially, meaning precedes validation. Bureaucratically, validation follows conformity. Anyone who insists on truth before acceptance will experience friction as a personal cost.

This is why the good fight rarely feels good. Reformers are sidelined before they are celebrated. Truth-tellers appear abrasive before they are vindicated. Builders endure long stretches where nothing “works” and no one is grateful. The humiliation is not incidental—it is the price of remaining oriented toward reality while others protect comforting illusions.

Boyd never “won” in the way institutions define victory. But he endured long enough to change how others thought. That endurance—quiet, stubborn, and often humiliating—is what the good fight actually looks like when the adversary is not incompetence, but comfort.

In that sense, humiliation is not the opposite of the good fight.

It is its signature.