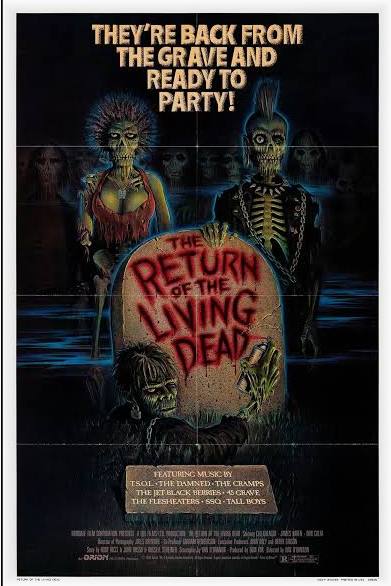

Punk did not begin in 1976 with a sneer, a safety pin, or a Sex Pistols B-side. Those were sparks, not origins. As Chris Sullivan argues in a recent essay—and expands powerfully in his book Punk: The Last Word—punk is not a genre, a haircut, or a moment in British cultural history. It is a mindset. A way of confronting authority, uncertainty, and stagnation that predates amplifiers and persists long after the last power chord fades out. As a character memorably puts it in the 1980s classic The Return of the Living Dead, “It’s not a fashion, it’s a lifestyle.” Stripped of its pop-cultural mythology, punk reveals itself as something far more durable and far more consequential.

At its core, punk is the refusal to accept inherited authority without interrogation, the willingness to act without permission, and the courage to live with the consequences of that choice. That insight matters far beyond music or fashion. Once detached from leather jackets and club scenes, punk begins to look uncomfortably familiar to philosophers, strategists, innovators, and leaders who altered history not by preserving systems, but by disrupting the assumptions beneath them. This is where Sullivan’s historical excavation becomes more than cultural commentary. It becomes a leadership lesson.

Sullivan’s argument works because it refuses nostalgia. Rather than canonizing punk as a frozen artifact of the 1970s, he treats it as a recurring human posture—one that reappears whenever institutions calcify and authority mistakes longevity for legitimacy. That posture is recognizable across eras and domains. It begins with a willingness to question what has been declared sacred, not out of cynicism, but out of a refusal to treat tradition as self-justifying. Punk-minded figures probe assumptions others no longer notice, asking why certain practices persist and whom they actually serve. From there comes the stripping away of pretense. Titles, rituals, and inherited narratives are exposed for what they often become over time: artifacts that once had purpose but now function primarily as performance. This unmasking is rarely polite, because pretense survives only so long as it remains unchallenged.

What follows is direct action. Punk does not wait for consensus, perfect information, or institutional blessing. It moves, tests, builds, speaks, and creates, accepting imperfection as the price of momentum. And finally, there is the cost. Those who adopt this posture almost always pay for it—through ridicule, marginalization, stalled advancement, or exile. History is unambiguous on this point. Punk energy is tolerated only after it can be safely romanticized. In real time, it is disruptive, uncomfortable, and unwelcome. Yet it is precisely this sequence—questioning, unmasking, acting, and absorbing the fallout—that repeatedly renews stagnant systems and prevents institutions from confusing longevity with legitimacy.

Seen through a leadership lens, punk is not rebellion for rebellion’s sake, nor is it insubordination. It is judgment exercised in advance of permission. Punk emerges when formal authority lags reality and when waiting for consensus carries greater risk than acting imperfectly. In such moments, punk figures are often the only leaders present—not because they hold positional power, but because they assume responsibility. They absorb personal risk in order to surface uncomfortable truths, test new paths forward, and force institutions to confront conditions they would rather ignore. Punk, in this sense, is leadership under uncertainty.

From a strategic perspective, punk functions as adaptive pressure applied to stagnant systems. It surfaces when rules outlive their purpose, when expertise becomes gatekeeping rather than guidance, and when procedure substitutes for judgment. This is why punk figures tend to appear at moments of civilizational strain—when dominant orders can no longer explain the world they claim to manage, yet continue to enforce rituals of control as if explanation alone were sufficient.

Sullivan’s greatest contribution is tracing this posture far beyond guitars and clubs, locating it in thinkers and actors whose lives unsettled the moral and intellectual comfort of their age. Socrates, barefoot, penniless, and relentlessly irritating, did not write manifestos or lead movements. He asked questions publicly and persistently, without regard for status. For this, he was executed. Strategically, Socrates represents epistemic disruption—the moment when asking “why?” becomes more dangerous than proposing alternatives. Diogenes went further, weaponizing ridicule to expose hierarchy as performance. Modern institutions still fear this type of figure because satire collapses authority faster than argument.

The same logic appears in less comfortable historical cases. The pirates Sullivan describes were not merely criminals; they were organizational innovators operating at the margins of empire. Democratic captaincy, shared plunder, and compensation for the wounded were radical governance experiments at sea. From a leadership perspective, these pirate republics reveal a recurring truth: legitimacy follows fairness and competence, not titles. Hierarchy without trust collapses under stress.

Punk flourishes most visibly in the creative arts, where deviation cannot be fully regulated. Caravaggio shattered artistic and moral conventions, forcing religious institutions to confront the humanity they preferred to sanitize. Gustave Courbet challenged elite control of meaning by insisting that art depict the real rather than the ideal, paying for it with imprisonment and exile. Arthur Rimbaud revolutionized poetry by eighteen, then refused to be captured by his own success. In each case, punk democratized creation, and institutions responded by criminalizing or expelling the act.

One of Sullivan’s most revealing figures is Vivienne Westwood, not simply because of her cultural impact, but because of the way she lived her dissent. Westwood refused to professionalize rebellion or make it safe for institutional consumption. That refusal made her iconic—and dangerous. Her statement, “I just have to do it,” was not a slogan but an ethical declaration. It captured punk not as performance, but as obligation: once something is seen clearly, action becomes unavoidable, regardless of cost. From a leadership standpoint, this exposes a tension institutions prefer to avoid. Authentic leadership is destabilizing. Conformity is rewarded. Integrity, when it challenges power or norms, is often punished. This is why organizations praise innovation in the abstract while remaining deeply uncomfortable with the people who actually produce it.

Punk is not fixed on the ideological spectrum; it migrates. It appears wherever authority becomes performative, moral certainty hardens into identity, and dissent is punished more for tone than for substance. At different moments, insurgent energy has attached itself to movements across the political landscape—not because of policy content, but because those movements challenged elite consensus and credentialed gatekeeping. But punk energy is fragile. The moment disruption is mistaken for righteousness, or insurgency calcifies into spectacle and orthodoxy, it ceases to be punk and becomes a counter-bureaucracy. Punk expires when it stops questioning itself.

This helps clarify a common confusion. Punk is not simply counterculture. Counterculture denotes opposition to dominant norms or aesthetics and can persist indefinitely without producing change. Punk is counterculture plus action, cost, and institutional pressure. Where counterculture often hardens into identity or symbolism, punk manifests as behavior—acting without permission, accepting personal risk, and forcing institutions to respond. Counterculture may coexist with systems; punk cannot. It is either absorbed, expelled, or suppressed, but never ignored. Counterculture resists norms. Punk tests them and compels reality to enter the system.

Punk also looks different today because the cultural baseline has shifted. Loud transgression and nihilistic rebellion have largely been absorbed, monetized, and ritualized. In a media and political environment that rewards cynicism, irony, outrage, and dehumanization, punk now appears where behavior violates the dominant incentive structure. In such a context, trust can be punk. Earnestness can be punk. Refusing to dehumanize can be punk—not as naïveté, but as disciplined resistance. When suspicion and contempt become institutionalized, choosing moral seriousness and restraint becomes countercultural leadership.

All of this leads to a final clarification. Punk is not a personality type, an identity, or a standing role within an institution. It is a mode of leadership—a tool that becomes necessary under specific conditions. Some personalities may be more inclined to reach for that tool, but no healthy system should assign “punk” as someone’s permanent job. Punk is situational and episodic. The same leader may need to violate norms and act early in one moment, then stabilize and institutionalize in the next. Institutions fail when they suppress this mode entirely or trap certain people in it until they burn out or are expelled.

This also explains why punk is so elusive, and why it resembles humility. Punk exists only in relation to power. The moment it is named, claimed, or celebrated, it collapses into performance. What made the action punk was precisely that it was unauthorized and unvalidated. Once institutionalized, punk stops exerting pressure and becomes safe. It is unstable not because it lacks coherence, but because it is relational. It exists only when there is a gap between authority and lived reality, and it disappears once that gap is acknowledged or domesticated.

Punk, then, is not a permanent identity but a phase in a renewal cycle. Its function is to surface misalignment, break monopolies on meaning, and reintroduce movement. Once it succeeds—once it is codified, taught, or celebrated—it ceases to be punk. That is not failure; it is completion. Healthy institutions do not need everyone to be punk, nor could they survive that. They need punk energy at the margins, stabilizing energy at the core, and the ability to rotate people between those roles without destroying them.

Institutions fail when they romanticize punk in hindsight, punish it in real time, and then wonder why judgment, innovation, and moral seriousness disappear. Seen this way, punk is not ideology or culture. It is a temporary authorization to violate norms in service of renewal. For leaders, innovators, and strategists, the question is not whether punk belongs in serious institutions. The question is whether institutions that suppress unauthorized judgment, early experimentation, and moral friction can adapt fast enough to survive. History suggests they cannot.