I, along with so many of my peers, have been professionally involved in, adjacent to, or forced to reckon with American regime-change efforts since Panama. I was a young officer when Noriega was removed quickly, decisively, and—by historical standards—cleanly, an experience that would later prove to be the exception rather than the rule. From Panama to Baghdad, from Kabul to Tripoli, the pattern has been remarkably consistent. The United States is very good at removing regimes. It is far less successful at managing what comes after. Again and again, it is not the initial operation that defines the conflict, but the political, social, and regional consequences that follow—and those consequences almost always arrive whether we plan for them or not.

That is why any serious discussion of a potential conflict with Venezuela must begin before the first strike is ever contemplated—by confronting the political, regional, and humanitarian consequences that will follow. The danger is not that the United States would fail militarily. The danger is that it would succeed tactically while unleashing second- and third-order effects that destabilize an entire region, empower non-state actors, and quietly hand strategic advantage to competitors—without ever formally losing a war.

Venezuela is not Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Libya, or Panama. But the aftermath of intervention tends to rhyme even when the context does not. Venezuela sits at a convergence point of fragility that should give strategists pause. State authority is already uneven beyond Caracas, borders with Colombia and Brazil are porous, maritime proximity ties instability directly to the Caribbean, and more than seven million Venezuelans have already fled. Unlike Panama in 1989—where institutions largely survived regime removal—Venezuela would enter any conflict already fractured. Power would not disappear; it would fragment.

The most immediate second-order effect would be migration, but without the safety valves that existed in earlier interventions. Historically, instability flowed outward and was eventually absorbed, in part, by the United States and/or Europe. That outlet is now constrained. If conflict accelerates Venezuelan displacement while the United States hardens its border posture, population flows will concentrate regionally rather than dissipate globally. Colombia absorbs the first shock, followed by Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Brazil, and smaller Caribbean states. Migration ceases to be a purely humanitarian challenge and becomes a governance crisis—overwhelming public services, hardening domestic politics, and forcing zero-sum tradeoffs across Latin America.

As central authority weakens, border regions do not become empty spaces. They become power centers. The Colombia–Venezuela frontier already hosts armed groups, traffickers, and hybrid criminal-political actors who thrive in ambiguity. Conflict expands their operating space, turning borderlands into semi-autonomous economic and security ecosystems. This pattern is familiar. Post-2003 Iraq and post-2011 Libya demonstrated how quickly illicit governance structures harden once the state recedes. These systems outlast regimes and are far harder to dismantle than the governments that preceded them.

Energy shock introduces another destabilizing layer, particularly for Cuba. Cuban economic stability and electricity generation remain heavily dependent on Venezuelan oil. Disruption cascades quickly into blackouts, economic contraction, social unrest, and outward migration pressure. In this scenario, Cuba is not an observer but a secondary casualty, one whose instability carries its own regional consequences. Regime change rarely stays confined to the borders on the map.

The Missing Variable: What Is the End State?

Before any strike, the United States has to say….clearly…. what it wants. “Stopping drugs” is not an end state; it is a slogan. As I argued in a War On the Rocks piece Strategy or Spectacle in South America?, Venezuela is merely a transit node in a transnational cocaine system, with a significant share of that flow bound for Europe rather than the United States. Treating Venezuela as the center of gravity risks solving the wrong problem at high cost. If the problem is a network, attacking a waypoint may create disruption—but disruption is not the same as strategic effect.

If the objective is counternarcotics, then the theory of change must be explicit and testable. Military action against Venezuelan targets must demonstrate how it measurably degrades trafficking networks over time; affecting price, purity, routes, organizational resilience, and market behavior—rather than merely producing seizures, arrests, or short-term disruption. Absent that linkage, kinetic action risks becoming spectacle rather than strategy.

This immediately raises a requirement the United States has historically struggled to meet: publicly defensible metrics. If counternarcotics is the justification, success cannot be measured in tonnage seized, targets struck, or sorties flown. It must be measured in outcomes that are durable, visible, and shareable with domestic and international audiences. That means tracking sustained changes in wholesale and street-level pricing, shifts in purity and adulteration, network fragmentation or consolidation, rerouting behavior, financial flows, and time-to-reconstitution for disrupted organizations. These metrics are imperfect, but they are strategically meaningful. Without them, the United States cannot credibly demonstrate that military action is producing anything other than tactical noise.

Which raises the uncomfortable possibility that the real objective is not drugs at all, but coercion, or regime change. If that is the intent, it must be owned honestly. Regime change is not a strike package; it is a political project with downstream obligations. The historical record since Panama is consistent. Phase III—major combat operations designed to break regime control—is almost always over-planned. Phase IV—stabilization, governance, security, and legitimacy—is treated as an afterthought. Yet Phase IV is where wars are won or lost.

Put simply, Phase III is about defeating the regime. Phase IV is about preventing the vacuum. Phase III ends when organized resistance collapses. Phase IV begins immediately and lasts indefinitely, encompassing security provision, border control, humanitarian relief, institutional continuity, economic stabilization, and narrative legitimacy. If the United States is not prepared to resource Phase IV from the outset, then it is not prepared to intervene—because Phase IV is not a sequel to the war; it is the war.

Any credible Phase IV plan therefore requires an interagency task force from day one—State, Treasury, Justice, DHS, intelligence, and development authorities. Whether USAID exists as a standalone institution or has been reorganized is almost beside the point; the function still exists, and without it the campaign collapses under its own weight. Humanitarian relief, migration management, economic stabilization, and institutional support cannot be bolted on after the fact. They must be integrated into campaign design, with clear authorities, funding lines, and accountability.

Just as importantly, the information environment cannot be treated as an afterthought. Strategic competitors benefit without firing a shot. Russia raises U.S. costs through intelligence support, cyber activity, and narrative warfare, reinforcing a perception of American disruption without accountability. China positions itself as the defender of sovereignty and a future economic stabilizer, playing a patient, long-term game while Washington absorbs responsibility for disorder. This is not merely propaganda or diplomacy; it is cognitive warfare—shaping perceptions of legitimacy, causality, and blame across regional and global audiences. In that fight, ambiguity about end state and metrics is not neutral; it is exploitable.

Risk Matrix: Who Bears the Cost?

When discussions of intervention focus narrowly on feasibility or escalation control, they obscure a more consequential question: who actually pays for the second- and third-order effects once violence begins? Viewed through a regional and systemic lens, the answer is consistent with past experience.

| Actor / Country | Migration Pressure | Security Spillover | Economic Shock | Political / Legitimacy Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venezuela | Extreme | Extreme | Extreme | Regime fracture and internal collapse |

| Colombia | Very High | High | Medium | Severe domestic and border instability |

| Peru / Ecuador / Chile | High | Medium | Medium | Medium–High political strain |

| Brazil (North) | Medium | Medium | Low | Persistent regional pressure |

| Caribbean States | Medium | Low–Medium | High | Systemic fragility |

| Cuba | Medium | Low | Very High | Acute regime and social risk |

| United States | Low | Low | Low | High strategic and legitimacy risk |

| Russia / China | None | None | Low | Strategic and cognitive opportunity |

The asymmetry is unmistakable. The United States bears relatively little direct material cost but assumes the greatest reputational and legitimacy burden if objectives are unclear or outcomes deteriorate. Russia and China, by contrast, incur minimal downside while benefiting strategically—particularly in the cognitive domain, where narratives of intervention without accountability travel faster than facts.

This distribution of cost forces the central strategic question: what end state justifies this risk?

End State → Metrics → Interagency Lead

If the end state is ambiguous, metrics become performative and responsibility fragments across the bureaucracy. Strategy demands alignment between political objective, measures of success, and institutional ownership.

| Declared End State | What Must Change (Metrics) | Primary Interagency Leads |

|---|---|---|

| Counternarcotics | Sustained price increases; sustained purity volatility or decline; durable route disruption; longer network reconstitution timelines; degraded financial flows | Treasury, DOJ/DEA, DHS/Coast Guard, State, Intelligence Community |

| Coercion / Behavior Change | Verifiable policy concessions; reduced external destabilization; compliance timelines; enforcement and verification mechanisms | State, Treasury, Intelligence Community, DoD |

| Regime Change | Security provision; border control; essential services continuity; refugee flow stabilization; regional spillover containment; legitimacy indicators | State, DoD, Treasury, DHS, development authorities, Intelligence Community |

The contrast is revealing. A counternarcotics end state is about markets and networks, not regimes. A coercive end state is about behavioral change, not punishment. A regime-change end state is about order after collapse, not collapse itself. Each demands different tools, different metrics, and different leadership. None succeed without explicit Phase IVownership.

Comparative Lessons: Patterns, Not Parallels

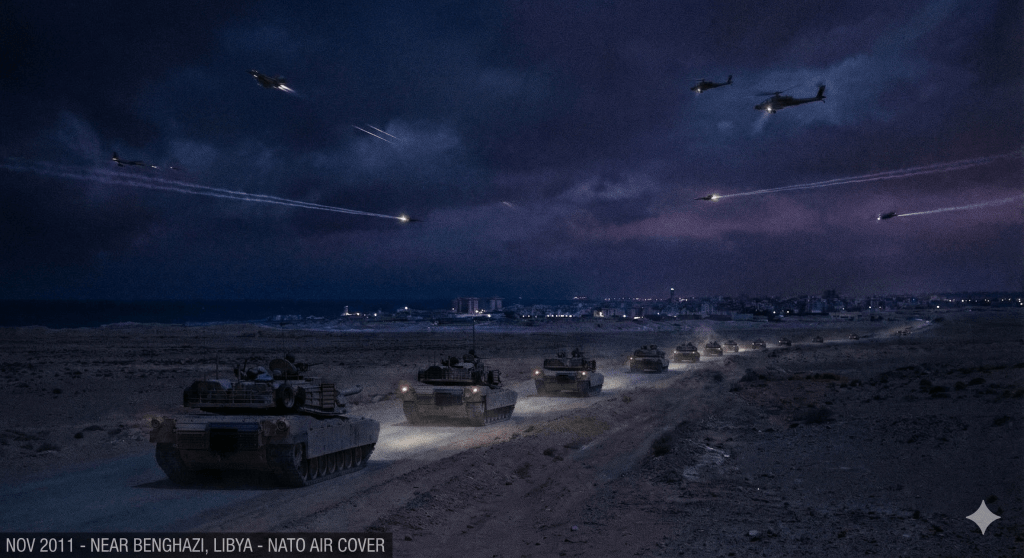

Panama demonstrated that regime change can succeed when institutions survive, spillover is minimal, and displacement is negligible. Iraq demonstrated that removing a regime is far easier than reconstructing political authority. Afghanistan showed that legitimacy cannot be imported faster than it can be built. Libya revealed how state collapse produces durable regional instability and illicit governance. Syria proved that refugee flows can destabilize regions far removed from the battlefield.

Venezuela most closely resembles Libya and Syria, not Panama. The lesson is not that intervention always fails, but that post-intervention dynamics—not battlefield success—determine strategic outcomes.

Regime change is an event. Instability is a process. The United States has mastered the former and consistently underestimated the latter. Venezuela should not be evaluated as a discrete operation, but as a systemic stress test for the hemisphere. The real question is not whether a regime could fall. It is whether the US is prepared—politically, economically, strategically, and cognitively—to own the second- and third-order effects that would inevitably follow. History suggests that when those effects are treated as downstream concerns, they become the defining features of the conflict itself.