Understanding the current geopolitical landscape begins with examining the strategic chessboard defined by Washington and Beijing. Their rivalry now shapes the structure of global economics, the tempo of military modernization, the direction of technological innovation, and the alignment of diplomatic blocs. Few bilateral relationships in modern history have exerted such sweeping influence. The international system is being pulled—quietly, steadily, and often forcefully—into the gravitational field created by these two powers.

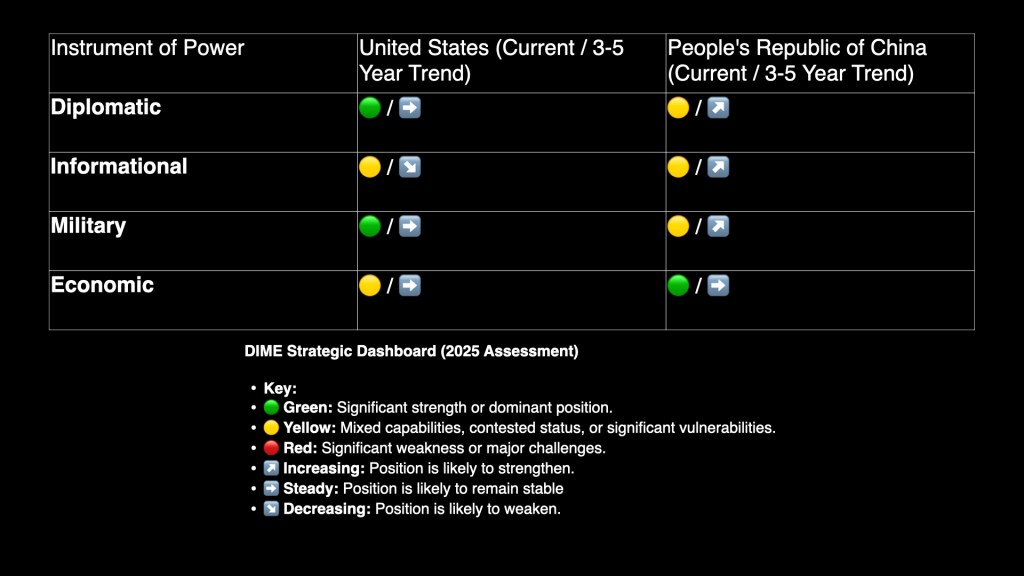

Characterizing this rivalry requires more than a catalog of weapons or economic statistics. National power is multidimensional, interdependent, and constantly evolving. For years, strategic practitioners across government have used the DIME framework—Diplomatic, Informational, Military, Economic—to organize and assess these dimensions. Although imperfect and prone to misuse when treated as a checklist, DIME becomes a powerful analytical tool when understood as a system of interconnected levers. Through this systemic interpretation, the U.S.–China competition emerges not as a static contest but as an integrated struggle shaped by alignment, adaptation, and strategic purpose.

This analysis is a simplistic attempt to map the emerging world order.

The United States continues to hold some of the strongest structural advantages on the planet: a globally deployed and combat-experienced military, the most extensive alliance network in human history, and unparalleled leverage over the world’s financial architecture.

China, meanwhile, is compressing decades of development into a single generation, propelled by a centrally coordinated strategy and a political leadership convinced that its window to achieve core objectives is narrowing. These contrasting trajectories—American strategic drift and Chinese strategic compression—are generating a global environment marked by tension, acceleration, and uncertainty.

The world is moving toward a more contested strategic equilibrium.

The Diplomatic Contest: Depth vs. Reach (D)

Diplomacy serves as the conductor of national power. It integrates direction, synchronizes resources, and shapes the strategic environment in ways no other instrument can match. Viewing diplomacy as merely one tool within the DIME framework overlooks its central role in orchestrating the other three dimensions.

On this front, the United States still commands unmatched diplomatic depth. NATO remains the most sophisticated military alliance ever created. Formal defense treaties with Japan, South Korea, Australia, and other partners extend American influence across multiple theaters. These alliances bring shared intelligence, interoperable military capability, and political cohesion developed over generations. They provide unique advantages that China cannot replicate.

Yet this system also shows signs of strain. A decade of inconsistent engagement with international institutions, fluctuating foreign-policy priorities, and episodic unilateralism has created uncertainty among even the closest allies. Some partners have begun incremental hedging strategies, balancing cooperation with Washington against economic ties to Beijing. The network remains exceptionally strong but increasingly requires deliberate strategic maintenance.

China’s diplomatic expansion follows a different model—broad, transactional, and economically anchored. The Belt and Road Initiative has woven more than 150 countries into long-term infrastructure, energy, and logistics commitments. Within the United Nations system, Beijing has systematically increased its representation and influence, promoting interpretations of sovereignty and governance aligned with its interests. Across the Global South, Chinese diplomatic engagement often fills gaps left by Western hesitancy or conditional aid.

However, the quality of these relationships differs markedly from the U.S. alliance structure. Chinese partnerships tend to be economic rather than security-centered, and political loyalty remains shallow. In a major crisis, few BRI participants would risk sanctions, instability, or military entanglement on Beijing’s behalf.

The United States leads alliances; China manages dependencies.

The distinction is strategic and consequential.

The Information Domain: Platform Power vs. Narrative Power (I)

If diplomacy provides structure, information provides tone and psychological shape to global interaction. In this domain, the United States and China engage in an asymmetric contest defined by contrasting strengths and vulnerabilities.

The United States retains mastery over the world’s information platforms. American companies dominate global search, mobile ecosystems, cloud infrastructure, film and media, and academic research. Cultural gravity—from Hollywood to Silicon Valley—continues to lean toward American ideals, creativity, and narratives.

Yet openness creates exposure. The U.S. information environment has become increasingly polarized, fragmenting the national narrative and reducing global confidence. Adversaries exploit this openness to amplify division and uncertainty. Government efforts to coordinate counter-disinformation strategies remain fragmented and reactive.

China operates according to a fundamentally different model. It does not dominate global platforms, so it focuses on controlling content, both internally and externally. Under the “Three Warfares” doctrine—public opinion, psychological operations, and lawfare—China has constructed the world’s most extensive authoritarian influence apparatus. Components include:

- State-directed media with global reach

- Online influence farms and coordinated digital campaigns

- AI-generated personas and targeted psychological operations

- TikTok and other platforms as vectors for both cultural influence and narrative shaping

- Legal and regulatory pressure to reshape information norms in international institutions

Domestically, China maintains strict control over the information environment, limiting dissent and shaping public perception. Internationally, it deploys increasingly sophisticated influence capabilities that exploit the openness of democratic systems.

This creates a central paradox of the information age:

Democratic openness provides resilience but invites manipulation; authoritarian control provides coherence but lacks credibility.

The Military Balance: Global Superpower vs. Regional Titan (M)

The U.S. military remains the most capable global force in existence. Its defense budget exceeds those of the next several nations combined. It maintains global basing, unmatched power projection, and superior joint operational experience. American advantages in stealth technology, undersea warfare, and nuclear-powered platforms remain significant.

However, military power is contextual. In the Indo-Pacific—the theater most likely to define the future balance—China has achieved substantial operational advantages. The PLA Rocket Force now fields missiles capable of targeting U.S. carriers and bases at long range. China’s shipbuilding capacity exceeds that of the United States by orders of magnitude. In hypersonics, electronic warfare, and certain forms of autonomous targeting, the PLA is rapidly closing gaps.

The doctrine of “intelligentized warfare” seeks to unify artificial intelligence, automation, and sensor-driven precision into an integrated military ecosystem. If fully realized, this would represent a qualitative shift in how wars are planned and fought.

At the same time, the United States faces a critical industrial vulnerability: dependence on rare earth mineral processing overwhelmingly controlled by China. Advanced U.S. weapons systems—from precision munitions to aircraft components—rely on supply chains that could be disrupted during a crisis. In a prolonged conflict, technological superiority would matter less than the ability to sustain production—an area where China holds significant advantage.

China, however, lacks combat experience. Its joint command structure is new, its logistics remain untested under wartime conditions, and its nuclear C2 architecture has never been stressed in crisis.

The U.S. remains the world’s primary global military power.

China has become the dominant regional military power in East Asia.

This dual reality defines the strategic environment.

The Economic Arena: The Dollar vs. the Workshop of the World (E)

The economic competition between the United States and China is not simply a matter of GDP. It concerns the architecture of global finance, trade networks, supply chains, and emerging technological ecosystems.

The United States possesses the world’s most powerful economic instrument: the dollar. As long as the dollar remains the global reserve currency, Washington retains unparalleled sanctions authority and global financial leverage. American innovation ecosystems continue to lead in frontier technologies including AI, biotechnology, aerospace, and advanced software.

Yet structural vulnerabilities persist. Critical supply chains have migrated offshore. Domestic manufacturing capacity has hollowed out. Political polarization introduces volatility into tariff policy and regulatory frameworks. Efforts to re-shore semiconductor production and critical mineral processing will take years to mature.

China’s economy delivers the opposite profile: immense manufacturing scale, dominance over global industrial inputs (including rare earth processing), and deep integration into global value chains. Its infrastructure, logistics, and export capacity exceed those of any other nation. However, the Chinese economy now faces significant structural headwinds—rising debt, demographic contraction, youth unemployment, and instability in the property sector.

To mitigate exposure to U.S. financial power, Beijing is constructing parallel systems: the digital yuan, alternative payments networks, and trade settlement pipelines that bypass the dollar. This constitutes a long-term strategy to erode American financial coercive power.

The United States seeks supply-chain resilience.

China seeks financial insulation.

Both efforts will shape the next decade of global economic order.

Strategic Synthesis: Interlocking Instruments of Power

The most critical insight emerges not from examining each DIME category individually but from understanding how they interact.

China excels at integrating its instruments of power.

Economic investments support diplomatic leverage.

Technology companies support information campaigns.

Supply-chain dominance creates military vulnerabilities for adversaries.

Military modernization reinforces regional economic coercion.

This coherence amplifies the effectiveness of each instrument.

The United States possesses greater raw power across most dimensions, but that power is distributed across a fragmented political and institutional landscape. Diplomacy follows one rhythm, congressional politics another, private-sector innovation another still, and military strategy yet another. Misalignment dilutes strategic impact.

The contrast is clear:

China uses a higher percentage of the power it possesses.

The United States possesses more power than it effectively uses.

This is the defining tension of the decade ahead.

The Emerging Horizon: Strategic Compression and Strategic Drift

China now operates under the psychological pressure of a narrowing window—economic slowdown, demographic decline, concentrated political authority, and rising external resistance. Such conditions historically increase the probability of risk-acceptant behavior.

The United States confronts a different challenge: strategic drift. Its advantages remain extraordinary, but domestic division, industrial fragility, and inconsistent strategic focus create uncertainty about long-term resolve.

One state is driven by urgency.

The other is wrestling with coherence.

Their intersection will define the global system.

The Next 3–5 Years: A World Tilting Toward Contestation

The near future is unlikely to produce a decisive confrontation but will almost certainly generate intensified competition across all domains. Diplomatic blocs will harden. Information environments will polarize. Technological ecosystems will bifurcate. Economic interdependence will fray under national-security pressures. Military modernization will accelerate.

Crisis will become a more normal feature of the strategic landscape.

Misinterpretation and miscalculation will increase.

The margin for strategic error will shrink.

The direction of the global order will be determined not by any single instrument of power but by the ability of states to integrate diplomacy, information influence, military capability, and economic strategy into coherent action.

In an era defined by both strategic compression and strategic drift, the decisive factor will not be possession of tools but the disciplined and imaginative integration of them.

That integration will determine the century.