1. Nietzsche’s Enduring Challenge to Conventional Leadership Paradigms

Few thinkers unsettle as profoundly as Friedrich Nietzsche. His writings on morality, truth, and meaning strike at the roots of Western culture, exposing what he saw as its life-denying foundations. He argued that conventional values—humility, obedience, piety—emerged not from vitality or strength but from what he called slave morality: the moral framework of the weak, built in opposition to the powerful and designed to suppress creativity, passion, and self-overcoming. Leadership, through Nietzsche’s lens, is not a matter of codified systems, efficiency, or even ethics as commonly defined. It is a matter of value creation—of forging new meanings in the shadow of what he famously called the “death of God”.

The death of God, as Nietzsche declared in The Gay Science, was not merely a theological claim but a cultural event: the collapse of transcendent, universally binding foundations of truth and morality. With those certainties dissolved, he saw modern life sliding into nihilism: the sense that existence lacks inherent meaning or purpose. For leaders—whether in bureaucracies, militaries, universities, or corporations—this cultural diagnosis poses a staggering challenge. If inherited frameworks no longer hold absolute authority, leadership cannot merely administer existing values. It must instead become a creative act, producing the very frameworks within which institutions and individuals find direction.

To lead in Nietzsche’s sense requires courage, strength, and imagination. It means questioning inherited assumptions, embracing conflict and struggle as sources of growth, and affirming life in all its messiness rather than retreating into safe conformity. It is, in short, to philosophize with a hammer—smashing the idols of stasis and mediocrity in order to create the conditions for vitality and excellence.

Leadership, when viewed through Nietzsche’s hammer, demands the courage to shatter convention and the vision to pursue the horizon of self-overcoming

2. Deconstructing Traditional Pillars: Truth, Morality, and Piety in Organizational Life

Nietzsche’s Critique of Truth and Perspectivism in Decision-Making

Nietzsche’s doctrine of perspectivism dismantles the Enlightenment’s faith in objective, universal truth. He declared, “There are no facts, only interpretations.” Truth, in his account, is always filtered through drives, instincts, and—crucially—power relations. What an institution calls “data” or “objectivity” is often the victory of one perspective over others, sanctioned by authority or tradition.

For organizations that pride themselves on being “data-driven” or “evidence-based,” this insight is unsettling. Data is never neutral; the categories chosen, the questions asked, and the interpretations permitted are already shaped by institutional priorities and entrenched power. Leaders who assume objectivity at face value risk becoming prisoners of their own illusions. A Nietzschean leader, by contrast cultivates an awareness of interpretation—asking not just what the numbers say, but whose interests they serve, what perspectives they silence, and how the organization’s orientation might be distorted by the comforts of consensus.

This does not mean collapsing into relativism where all views are equal. Nietzsche insisted some perspectives are “higher” than others: broader, more life-affirming, more capable of seeing the whole. Leadership, then, requires climbing to vantage points others cannot or will not reach—and having the courage to reorient the organization accordingly.

Slave Morality in Bureaucracy and Hierarchy

Nietzsche’s distinction between master morality and slave morality provides a sharp diagnostic tool for organizational life. Master morality arises from strength—it names good what is powerful, excellent, self-affirming. Slave morality, by contrast, arises from ressentiment: the bitterness of the weak toward the strong. It sanctifies meekness, obedience, humility, and conformity while branding vitality and ambition as “evil.”

Modern bureaucracies—be they corporate, military, or academic—often function as incubators of slave morality. Procedures and hierarchies discourage initiative; dissent is pathologized as insubordination; promotion favors compliance over creativity. Risk aversion becomes the operating norm. Ressentiment festers in office politics, passive-aggressive compliance, or the weaponization of “fairness” to drag down those who stand out.

The result is what Nietzsche might call a morality of mediocrity: an ethos that levels all differences, ensuring comfort for the herd at the cost of excellence. Such cultures cannot adapt dynamically to change, for they suppress precisely the energies—audacity, innovation, self-assertion—that renewal requires.

Piety, the Ascetic Ideal, and Organizational Sacred Cows

Nietzsche also warned against the ascetic ideal—the veneration of self-denial, purity, and unquestioned devotion to higher causes. In organizations, this takes the form of sacred cows: traditions maintained long past their usefulness, founding myths treated as untouchable, and groupthink that prizes orthodoxy over reality.

Even in secular contexts like academia, Nietzsche saw the persistence of ascetic patterns: the obsessive pursuit of “truth” detached from human flourishing, or the glorification of endless labor as virtue in itself. Leaders who cling to these ideals risk producing institutions that are lifelessly pious—devoted to empty rituals that sap vitality.

To counter this, Nietzsche urges leaders to philosophize with a hammer: to test the idols of the organization, discern which still ring true, and smash those that have become hollow. This is not reckless iconoclasm but disciplined courage—the refusal to let inherited forms dictate the horizon of possibility.

3. The Will to Power: Revaluing Strength, Vitality, and Creativity in Leadership

At the core of Nietzsche’s philosophy lies the Will to Power. Often misunderstood as mere domination, it is better understood as the fundamental drive of life to expand, overcome, and creatively shape both self and world. It is the energy of growth, transformation, and becoming.

For leadership, this means measuring “good” not by obedience to rules but by whether it enhances vitality: Does it make the organization stronger, more resilient, more capable of creating? Does it empower individuals to overcome limitations and actualize potential?

This perspective redefines leadership as creative destruction—a willingness to dismantle stagnant practices, even beloved traditions, in order to clear space for new forms of excellence. It resonates with Schumpeter’s later idea of “creative destruction” in economics, though Nietzsche had in mind not just markets but culture, morality, and the human spirit.

The Übermensch, Nietzsche’s ideal of the self-overcoming individual, embodies this principle. The Übermensch does not passively inherit values but creates them anew, affirming life in its fullness. For leaders, the challenge is to approximate this figure: to cultivate self-mastery, creativity, and the courage to craft meaning rather than rely on borrowed certainties.

At the same time, Nietzsche warns of the perils of the Will to Power untempered: it can devolve into tyranny, exploitation, or ego-driven domination. The corrective lies in self-overcoming—turning the Will inward, mastering one’s impulses, and creating values that affirm not only one’s own power but the flourishing of life in a broader sense.

4. Leadership as Becoming: The Dynamic Process of Self-Creation

Nietzsche saw human life not as static being but as becoming—an endless process of transformation. Leadership, in this light, is not a role or skillset but a perpetual act of self-creation and adaptation.

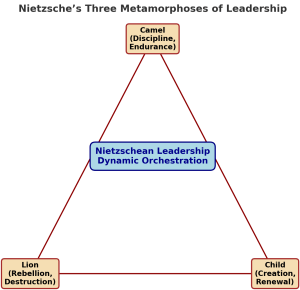

The Three Metamorphoses of Leadership Development

In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche sketches the three metamorphoses of the spirit—a parable for growth:

- Camel – bearing the heavy loads of tradition, duty, and discipline. Leaders begin by learning the system, submitting to its demands, and cultivating resilience.

- Lion – rebelling against the great dragon of “Thou Shalt.” Here the leader asserts independence, challenges orthodoxy, and says a sacred “No” to imposed values.

- Child – embodying innocence, play, and creation. The leader now says a sacred “Yes,” creating new values, institutions, and possibilities.

This arc suggests leadership is not mere skill acquisition but a spiritual journey: enduring burdens, breaking chains, and creating anew.

Strategic Agility: Nietzsche and the OODA Loop

Nietzsche’s emphasis on flux and becoming parallels modern strategic frameworks like John Boyd’s OODA Loop(Observe, Orient, Decide, Act). Boyd argued survival in conflict depends on cycling faster than opponents—constantly adapting to changing conditions. Nietzsche would agree: closed, rigid systems perish; open, adaptive systems thrive.

Both Nietzsche and Boyd insist that agility requires not just technical skill but philosophical courage—the willingness to embrace uncertainty, destroy outdated models, and reorient rapidly to new realities.

5. Eternal Recurrence as an Ethical Compass

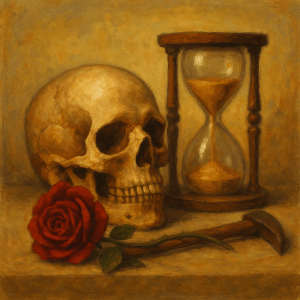

Perhaps Nietzsche’s most haunting idea is Eternal Recurrence: the thought experiment that every action, every decision, every moment of your life will repeat infinitely. Would you affirm your choices if you had to live them eternally?

For leaders, Eternal Recurrence becomes the ultimate ethical test. Short-term expediency is stripped away; what matters is whether one can will their legacy to recur forever. Decisions are judged not by temporary gains but by whether they create a world worth affirming again and again.

The ethic that arises here is amor fati—the love of one’s fate. For leaders, this means radical acceptance of responsibility: not only for successes but for failures, unintended consequences, and cultural legacies. It demands building institutions, making choices, and shaping cultures one could joyfully will to endure eternally.

6. Nietzschean Leadership in Modern Contexts

Bureaucratic Environments: Intelligent Disobedience

Weber’s “iron cage” of bureaucracy exemplifies slave morality: rational, efficient, but stifling. Nietzsche’s remedy is cultivating individuals who practice intelligent disobedience—the courage to say “No” when rules become life-denying. Organizations that reward such moral courage avoid the stagnation of blind conformity and remain adaptive in crisis.

Military Strategy: Conflict and Growth

Nietzsche viewed conflict not as purely destructive but as a crucible for strength. A Nietzschean military leader would see war not as an end in itself but as a field where vitality, creativity, and adaptability are tested. Peace without vitality, Nietzsche warned, breeds decadence. The challenge is cultivating a force capable of struggle without glorifying destruction for its own sake.

Academic Leadership: Beyond the Ascetic Ideal

In universities, Nietzsche saw the danger of knowledge pursued as sterile asceticism. A Nietzschean academic leader would smash idols of credentialism and bureaucratic learning, instead nurturing intellectual hunger and cultivating “free spirits.” Education should feed those who truly hunger for knowledge, not standardize students into conformity.

Case Studies: Jobs and Boyd

Figures like Steve Jobs embody aspects of Nietzsche’s leadership: creative destruction, audacity, disdain for convention. Yet his legacy raises Nietzsche’s ethical question: was his Will to Power life-affirming or merely market-dominating?

By contrast, John Boyd’s OODA framework resonates more deeply with Nietzsche: dynamic, adaptive, relentlessly questioning. Boyd’s insistence that survival depends on adaptability reflects Nietzsche’s affirmation of becoming.

The lesson is clear: many “disruptive” leaders wield the lion’s hammer of destruction but fail to reach the child’s innocent creation or the camel’s disciplined endurance. True Nietzschean leadership requires all three metamorphoses.

7. Navigating the Shadows: Responsible Application

Nietzsche is dangerous. His writings have been misused—from fascist misreadings to Silicon Valley’s cult of disruption. Leaders must guard against reducing Nietzsche to elitism, nihilistic relativism, or justification for tyranny.

The challenge is to harness his insights responsibly:

- Recognizing ressentiment as a corrosive force in organizations.

- Balancing the Will to Power with ethical self-overcoming.

- Democratizing the ideal of self-overcoming so that all members of an organization are invited to pursue excellence, rather than elevating a chosen few.

Nietzsche’s “aristocracy of spirit” need not conflict with modern egalitarianism if reinterpreted as a call for each person to cultivate their highest potential. The challenge is not domination but creating cultures where vitality flourishes at every level.

8. In The End: Forging Leadership Beyond Conventional Morality

Nietzsche offers no easy formulas for leadership. Instead, he poses disturbing questions: What values sustain your organization? Are they life-affirming or life-denying? Do you lead from ressentiment or from strength? Could you will your legacy to recur eternally?

To lead with Nietzsche’s hammer is to smash idols of mediocrity, conformity, and empty piety. To lead with his horizon is to affirm becoming—to create values, institutions, and futures that embody vitality, creativity, and courage.

Such leadership is demanding, fraught with peril, and resistant to codification. But in an age of nihilism, where inherited frameworks crumble and bureaucratic inertia dominates, Nietzsche’s challenge is indispensable. He compels us not to administer the past but to create the future—to lead not only competently but courageously, creatively, and affirmatively.

The hammer clears the ground; the horizon calls us forward.