“They sentenced me to twenty years of boredom / For trying to change the system from within.”

— Leonard Cohen, “First We Take Manhattan”

Leonard Cohen’s “First We Take Manhattan” is not merely a song—it is a philosophical insurgency. Released in 1988 and written a few years earlier, in the waning days of the Cold War, its haunting melody and cryptic lyrics offer more than poetic reflection. Beneath its noir veneer lies a blueprint for cognitive rebellion, a critique of institutional stagnation, and a subtle call to arms for those who seek not to destroy systems, but to redesign them from the inside out.

Cohen’s Silence and the Power of Ambiguity

Leonard Cohen said little about the meaning of “First We Take Manhattan,” and what he did say was deliberately unsettling. In one interview, he called it a “terrorist song”—but clarified that he meant terrorism not in a physical sense, but as a refusal to compromise. He admired the clarity of purpose that comes with such an uncompromising vision. It wasn’t an endorsement of violence—it was an artistic provocation.

Cohen’s reluctance to clarify the song’s meaning leaves it open to multiple readings: revolutionary, religious, psychological, poetic. That ambiguity is not a flaw—it is the very mechanism of the song’s strategic power. It orients the listener toward disorientation, drawing them into a cognitive loop that resists closure.

We don’t really know what this song is “about”—and perhaps we’re not meant to. In this sense, the song becomes an act of design rather than explanation. It invites not answers, but alignment. It whispers a campaign plan without revealing its true objective.

In that way, “First We Take Manhattan” is less a message and more a method. It teaches by evoking. It destabilizes in order to reorient.

Psychic Terrorism and the Legacy of the Iconoclast

Leonard Cohen was famously elusive when asked about the meaning of “First We Take Manhattan.” But in a rare backstage interview in 1988, he offered a glimpse—not a decoding, but a provocation:

“I think it means exactly what it says. It is a terrorist song. I think it’s a response to terrorism. There’s something about terrorism that I’ve always admired. The fact that there are no alibis or no compromises. That position is always very attractive. I don’t like it when it’s manifested on the physical plane – I don’t really enjoy the terrorist activities – but Psychic Terrorism. I remember there was a great poem by Irving Layton that I once read… it was ‘well, you guys blow up an occasional airline and kill a few children here and there’, he says. ‘But our terrorists, Jesus, Freud, Marx, Einstein. The whole world is still quaking.'”

This isn’t a defense of violence. It’s a call to a different kind of insurgency—intellectual, philosophical, spiritual. Cohen isn’t celebrating destruction. He’s aligning himself with those who unsettle civilization by reconfiguring meaning: Jesus, Freud, Marx, Einstein.

He may have been paraphrasing Irving Layton’s poem “The Search,” which ends with these lines:

Iconoclasts, dreamers, men who stood alone:

Freud and Marx, the great Maimonides

and Spinoza who defied even his own.

In my veins runs their rebellious blood.

This is the tradition Cohen claims—not of doctrinaires, but of heretical thinkers whose ideas detonated in the human mind. Psychic terrorism in this sense is the capacity to destabilize ossified truths, to collapse inherited worldviews, to demand a new orientation. It is the philosopher’s rebellion, the strategist’s paradox, the designer’s dangerous question.

“First We Take Manhattan” operates in exactly this register. It does not declare its intention outright. It haunts. It whispers. It orients the listener toward fracture, forcing them to make sense of contradiction. The song is not a theory. It is an event—a minor act of psychic terrorism embedded in pop culture.

And like all great insurgent works, its goal is not persuasion, but infection. It doesn’t want to convince. It wants to rewire.

Boredom as Exile: The Lament of the Reformer

“They sentenced me to twenty years of boredom / For trying to change the system from within.”

The song opens not with rage, but with resignation—a lament of the reformer crushed under the weight of the very system they hoped to improve. Boredom here is not passive; it is punitive. It is a sentence handed down by institutions to those who challenge their sacred assumptions too softly, too patiently, and with too much faith in procedure.

This is a familiar condition in any bureaucracy—military, academic, governmental—where change is invited but only within prescribed boundaries. The bored reformer is not defeated, but exiled. Their crime is not defiance but hope, misapplied within a system incapable of metabolizing true novelty.

Cohen’s line reads like a Clausewitzian friction not on the battlefield, but in the mind of the strategist. It is the slow erosion of meaning beneath the weight of compliance. Boredom, in this frame, is not disengagement—it is strategic death.

Rebellion as Orientation: Manhattan to Berlin

“First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin.”

This strange geographical progression is not about physical conquest. Manhattan and Berlin are symbolic targets—representing finance and ideology, illusion and memory, spectacle and fracture. To “take” them is not to invade, but to reclaim meaning from entrenched narratives.

The move from Manhattan to Berlin is also a shift from the polished veneer of modern power to the haunted ruins of its past. Manhattan is the performance of power; Berlin is its reckoning. Together, they sketch a map of the cognitive terrain in which power operates.

This is strategy not as force projection, but as epistemic disruption. The insurgent does not aim to defeat enemies in battle, but to reshape their ability to make sense of the world. It is strategy as re-orientation, the deepest level of John Boyd’s OODA loop—a war not over decisions, but over perceptions.

What Manhattan and Berlin Meant—Then

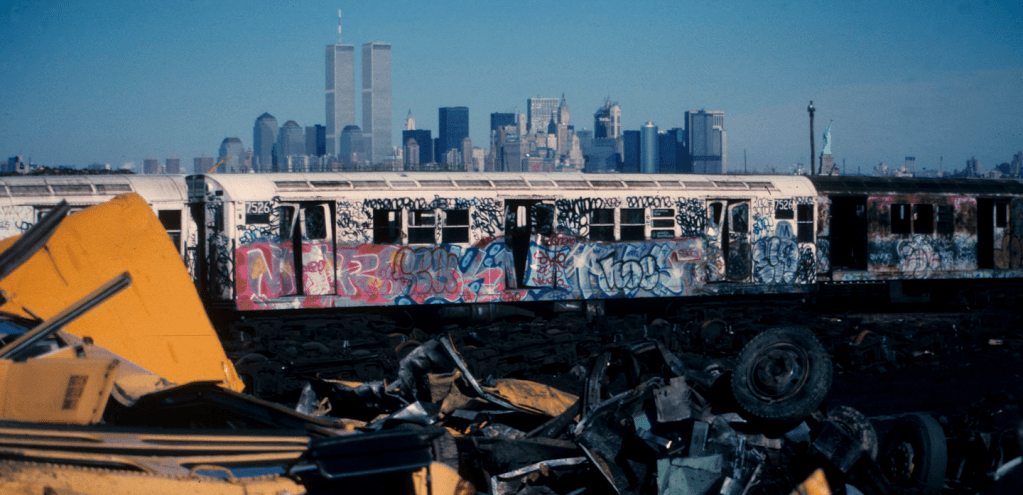

In 1986, when Leonard Cohen wrote “First We Take Manhattan,” these cities were not generic symbols. They were freighted with Cold War urgency and late-modern decay.

Manhattan was a paradox: the shining temple of Reagan-era finance and also a crumbling city battling crime, the crack epidemic, urban decay, and cultural fatigue. It was the era of Wall Street and Studio 54’s hangover, of economic bravado layered over social unraveling. The city was teetering on the edge of both resurgence and collapse. To “take Manhattan” was not a fantasy of conquest—it was a strike at the heart of a system obsessed with surface and increasingly hollow at its core.

Berlin, in contrast, was not metaphorical—it was literally divided. The Berlin Wall still stood, slicing the city—and the world—in half. East Berlin lived under the shadow of the Stasi and Soviet surveillance. West Berlin was a capitalist island surrounded by ideological hostility. The city was not a symbol of unity or reconciliation; it was a frozen frontline in the Cold War’s long psychological siege.

To “take Berlin” in 1986 was to challenge more than a city. It was to confront the hardened dualism of the postwar world—West versus East, freedom versus control, consumerism versus collectivism. It was the last holdout of a bipolar worldview on the verge of collapse.

In this context, Cohen’s campaign becomes a metaphysical sequence: first, unravel the illusion of capitalist modernity (Manhattan), then breach the front line of ideological division (Berlin). The sequence is not tactical but theological—a confrontation with the modern world’s twin idols.

Today, both cities have transformed. Manhattan has been financialized and sanitized; Berlin has been reunified and globalized. But in the mid-1980s, these places carried symbolic weight as crucibles of conflict. Cohen wasn’t writing a travel itinerary—he was mapping a war of meaning.

The Heretic’s Compass

“I’m guided by a signal in the heavens / I’m guided by this birthmark on my skin.”

These lines blend the transcendent and the embodied. The strategist Cohen sketches is not simply reactive, but guided—called. The “signal in the heavens” suggests a metaphysical purpose, while the “birthmark” grounds that mission in lived experience. Together, they evoke a kind of radical authenticity: fidelity to something beyond institutional approval, yet undeniable in its claim on the self.

This dual guidance mirrors the role of the heretical designer—those who operate within institutions yet are not fully of them. These are prophets in uniform, skeptics in sacred halls, thinkers who know the liturgy but refuse the idol.

Their rebellion is not arbitrary. It is born of alignment to deeper truths that institutions cannot always see. In this way, Cohen’s rebel becomes a Kierkegaardian knight of faith—isolated, misunderstood, but unshakably convicted.

Cognitive Warfare in a Minor Key

Much has been written in recent years about cognitive warfare—the idea that future conflict will revolve less around physical domains and more around perception, belief, and orientation. What Cohen intuited through song is now being codified in doctrine.

His use of slow, hypnotic rhythm and ambiguous lyrics enacts a kind of sonic disorientation. The listener is not led to a clear conclusion but suspended in meaning. There is no catharsis, only complexity. This is not accidental. It is design.

The song performs what strategic theorists might call a “moral offensive”: it undermines certainty, disrupts alignment, and inserts a new vector of interpretation. It is subversion without sabotage, insurgency without explosion.

If Clausewitz saw war as “an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will,” then cognitive war, in Cohen’s register, is an act of ambiguity to compel our enemy to question their own will.

Heretical Design and Strategic Liturgy

The strategist of the future is not merely a tactician or analyst. They must become what might be called a heretical designer—a figure who questions the assumptions of their own institution without abandoning its moral core.

This is a delicate balance. Heresy, after all, is only defined by the dominant orthodoxy. But in times of strategic stagnation, heresy may be the only path to renewal.

Cohen’s rebel offers a template for such figures. They are not nihilists. They are architects of new meaning. Their rejection of the system is not for the sake of chaos, but to create space for a better order—one that has not yet been spoken, but can be felt.

This is the heart of strategic design thinking: to resist the temptation of incrementalism and instead engage in destruction and creation, as Boyd called it. The strategist must be liturgist and heretic, systems thinker and saboteur of stale ideas.

The Whispered Threat

“I don’t like your fashion business, mister / I don’t like those drugs that keep you thin.”

This isn’t just social commentary—it’s a rejection of the aesthetic machinery of conformity. Cohen’s speaker refuses to play along. He is not just an outsider. He is something far more subversive: a stranger with intent. Not a man without belonging, but one who chooses not to belong to the system as it stands.

The rebel is always strange—not because they are eccentric, but because they refuse the comforting lies of familiarity. The stranger is not unknown; they are unassimilated. They belong to no tribe but the truth. In an age of branding, identity, and tribal allegiance, this is the most dangerous orientation of all.

Cohen’s protagonist doesn’t announce his revolution—he embodies it. He slips past the filters of polite society. He knows the code but speaks in riddles. He is not seeking integration; he is bearing witness. He is the signal institutions pretend not to hear—the whisper behind the doctrine, the threat beneath the anthem.

There’s no triumphant crescendo at the end of the song. Only a muttered, unnerving line:

“I don’t like what happened to my sister.”

It’s cryptic. Personal. Deeply human. And yet, it hints at something systemic—violation, injustice, grievance. This is not the battle cry of a general. It is the muttered resolve of a ghost. The real threat in “First We Take Manhattan” is not force—it is inevitability. Change is not coming from above. It is already here, dressed in black, walking softly, humming a tune you can’t forget.

Conclusion: A Liturgical Map for Strategists

Leonard Cohen’s “First We Take Manhattan” is not simply a protest song. It is a design artifact—a map for cognitive insurgency, a liturgy for heretical strategy, a whisper campaign against institutional stagnation.

Its lessons are clear, even if its meaning is not:

- Reform from within may result in exile, not impact.

- Strategy must begin not with tools, but with orientation.

- Rebellion must be grounded in conviction, not chaos.

- The most dangerous strategist is not the loudest, but the most disorienting.

In an era where warfare increasingly targets belief, perception, and meaning itself, Cohen’s strange, slow song may be one of the most strategically relevant anthems we have.

Because before you take the target… you take the mind.

And before you take the mind… you take the map.

And Cohen gave us one—hidden in plain sight.