The Hype Cycle: A Mirror for Institutional Behavior

In the world of technological forecasting and organizational transformation, few conceptual tools have had the lasting impact of the Gartner Hype Cycle. Introduced in the mid-1990s by the research and advisory firm Gartner, Inc., the Hype Cycle sought to explain a recurring pattern: how emerging technologies rise rapidly in attention and expectation, stumble through disappointment and disillusionment, and—if they survive, the valley of death—eventually mature into tools of real, productive value. This deceptively simple model has endured across industries as it captures something profoundly human about how organizations engage with change: so many times, we overpromise, we struggle, and sometimes, we adapt.

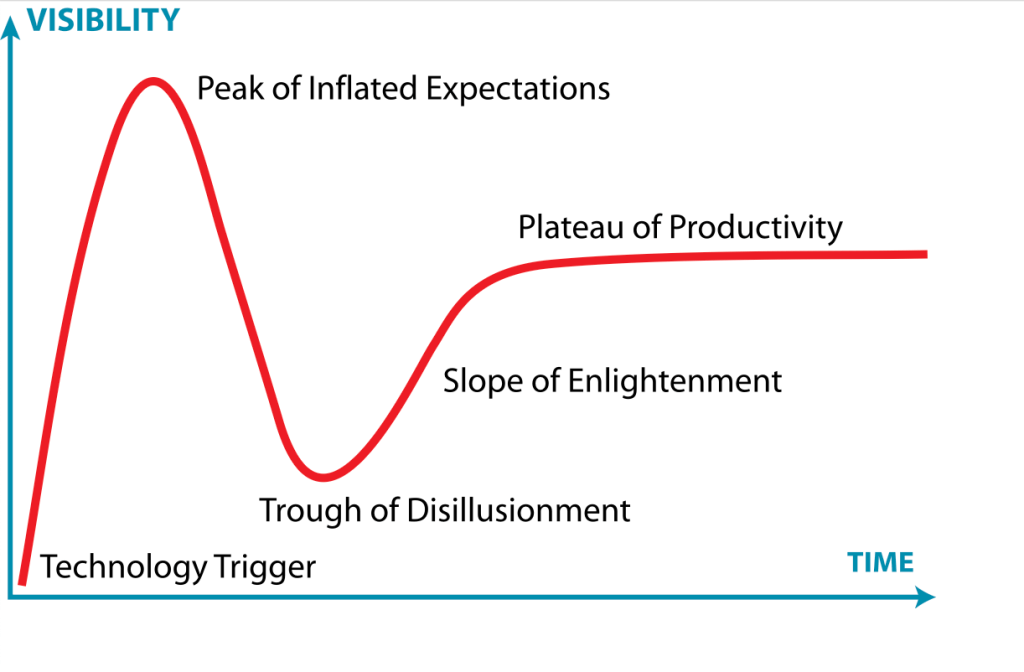

The Hype Cycle consists of five stages. First is the a) Innovation Trigger, where a breakthrough idea or capability—often rooted in science or strategy—enters the scene. A sudden burst of attention and potential follows, leading to the b) Peak of Inflated Expectations, a heady moment when aspirations soar beyond feasibility. Then comes the c) Trough of Disillusionment, as the real-world constraints of integration, sustainment, and scale expose the gaps between vision and execution. Slowly, if the idea has merit and champions, it moves up the d) Slope of Enlightenment, accumulating lessons and refinement. Finally, the innovation reaches the e) Plateau of Productivity—where it becomes part of the system and delivers meaningful results.

This cycle applies with particular clarity in the United States Air Force. As the service seeks to maintain relevance in an era defined by Great Power Competition, disruptive technology, and bureaucratic entropy, innovation has become a central tenet of its strategic vision. Across strategy documents, speeches, and service-level initiatives, innovation is celebrated as a lever of competitive advantage, even existential necessity. But when viewed through the Hype Cycle, the Air Force’s approach reveals a troubling pattern—one in which high-level enthusiasm often fails to translate into lasting, scaled outcomes. The cycle becomes not a pathway to maturity, but a treadmill of unmet expectations.

Innovation on Repeat: The Institutional Cycle of Excitement and Disillusionment

In recent years, the Air Force has declared its commitment to becoming a more agile, innovative force. Initiatives such as AFWERX, the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), and wing-level Spark Cells were created to support this agenda. These organizations, each in their own way, were designed to lower barriers to entry, connect talent to resources, and accelerate the adoption of new capabilities.

To be sure, many of these initiatives have delivered value. AFWERX pioneered the use of Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants to rapidly prototype and test technologies. DIU has served as a commercial bridge for dual-use technologies. Spark Cells have empowered junior Airmen to solve tactical problems at the wing-level.

Yet when we step back, we find ourselves caught in a recurring loop. Each new wave of innovation begins with rhetoric and enthusiasm. Senior leaders declare that “this time is different.” Airmen are encouraged to think big, challenge orthodoxy, and move fast. The service hosts pitch competitions, publishes glossy roadmaps, and heralds successes in polished reports. The expectations mount. And then, quietly, the friction sets in.

Program offices hesitate to take ownership. Funding dries up after the initial seed investment. Legal reviews stall contracting. Leadership turns over. The innovator PCS’s. The prototype that worked brilliantly in a lab or a local context fails to integrate into enterprise systems. The energy fades, the story goes quiet, and the Trough of Disillusionment deepens.

This cycle has real consequences. It burns out talent. It wastes time and money. And it erodes the credibility of innovation itself.

The Innovator’s Dilemma: Nowhere to Go with a Good Idea

The most critical impact of this repeated cycle may be the least visible: the slow demoralization of the individual innovator.

The Air Force rightly celebrates the ingenuity of its people. The belief that innovation can come from any rank, career field, or duty station is one of its most powerful cultural assets. But that belief is not enough. In practice, there is no clearly defined, cradle-to-scale pathway for Airmen who have good ideas. There is no consistent mentorship structure, no “innovation school,” no dedicated office whose mission is to shepherd promising concepts from the field to functional maturity. Instead, the landscape is fragmented, personality-driven, and dependent on ad hoc relationships.

This absence of structure is where the Hype Cycle intersects most painfully with the lived experience of the innovator. While institutions move through predictable stages of hype, burnout, and recovery, the Airman with the idea lives only once through that process. And if they are unsupported—if they lack the knowledge, resources, or guidance to bring their idea to life—they may never try again. Or worse, they may leave the service entirely, taking their mindset with them.

A Fractured Ecosystem: Brokers, Conveners, and Fragile Sparks

To understand the problem more deeply, we must look at the innovation ecosystem as it currently exists.

AFWERX and DIU have evolved into effective brokers—matching commercial solutions to defense needs and facilitating novel contracting methods. But they are not builders. They are not designed to incubate Airman-originated ideas or provide sustained support from concept to capability. Their function is transactional, not developmental.

Spark Cells, in contrast, are often portrayed as the heart of grassroots innovation. And at their best, they are. Located at the wing or maybe the squadron level, Spark Cells are built by volunteers who apply creativity to solve immediate problems. But these cells tend to be fragile. They often lack consistent funding, continuity of personnel, or linkage to higher-level priorities. Most Spark Cells die within two years—either when the founding members PCS or when local leadership shifts focus. They rarely transition ideas upward or outward. Their wins are local and fleeting.

Then there are entities like DEFENSEWERX and its embedded platforms such as SOFWERX. These public-private intermediaries are invaluable conveners. They facilitate challenges, hackathons, and problem curation events. They create collaboration space between operators, technologists, and entrepreneurs. Yet even here, the value proposition leans toward exploration, not execution. They provide the first mile of innovation, not the last.

The net effect is a sprawling innovation landscape with energy at the edges and inertia at the center. There is no “middle innovation layer”—no connective tissue that guides the Airman from inspiration to implementation. The result is predictable: innovation burnout. Airmen become disillusioned not because their ideas are bad, but because the system isn’t built to receive them.

Building the Middle Layer: From Fragmentation to Flow

If the service is serious about innovation—and if it wants to escape the gravitational pull of the Trough (aka The Valley of Death)—it must build the missing architecture.

First, the Air Force must establish a formal system of institutionalized mentorship. Just as operational squadrons rely on standardization and evaluation shops to guide aircrews through technical complexity, the innovation ecosystem needs its own cadre of professional navigators—Innovation Architects—who can guide Airmen through the intricacies of acquisition pathways, contracting vehicles, legal constraints, and funding strategies. These Architects should be embedded across MAJCOMs, and where feasible, within Numbered Air Forces and designated centers of excellence. Their role is not to act as gatekeepers or staff action officers, but as enablers and mentors—connective tissue between the front lines of innovation and the bureaucratic machinery required to bring good ideas to life. The tension they must manage is fundamental: to advise without co-opting, to mentor without micromanaging, and to serve the innovator rather than the system.

Second, the Air Force must establish a formal education track to cultivate innovation literacyacross the force. While Air University currently offers the prestigious Blue Horizons Fellowship through the Center for Strategy and Technology (CSAT), that program is intentionally limited in scope—highly selective, intellectually rich, and designed for a small cohort of 12 to 24 field-grade officers each year. What’s missing is a broader, scalable model that can reach a much wider audience across the enlisted and officer ranks.

This gap could be filled by creating an Airmen’s Innovation School—a PME-adjacent program that equips personnel with the tools of systems thinking, design methodologies, acquisition pathways, and strategic alignment. Importantly, this program should be inclusive of Airmen at various career stages, with a curriculum tailored to the Air Force’s operational and institutional realities. Not just theoretical frameworks, but practical, actionable pathways to move ideas from concept to capability.

Air University has already prototyped such an approach through the Innovator Development Course (IDC)—a grassroots, faculty-led effort built largely out of hide. Despite being staffed by academics juggling full teaching loads, IDC has now completed three iterations and received overwhelmingly positive feedback. The success of IDC shows both the appetite and the potential for institutionalizing innovation education at scale. Imagine a course that arms NCOs and junior officers with the knowledge and confidence to prototype ideas, align them with mission needs, and connect with technology accelerators across the Department of Defense. That future isn’t far off—but it needs to be resourced, legitimized, and scaled.

Third, the service must define clear, validated pathways from tactical idea to scaled capability. Spark Cells should have escalation routes into functional MAJCOMs and PEO offices. Promising ideas must be tracked, funded, and reviewed with an eye toward transition—not simply handed off and forgotten. Innovation should not rely on heroism; it should rely on process.

Fourth, the Air Force should institutionalize knowledge transfer. Each success and failure in innovation should be documented, analyzed, and shared. This “innovation case law” would help Airmen avoid reinvention, replicate best practices, and build a collective vocabulary around what works and what doesn’t. The current system is littered with lost knowledge and disconnected pilots. A repository of lessons, successes, and failures would provide the scaffolding for organizational learning.

Finally, the service must create incentives for innovation—not only in terms of awards and recognition, but in career progression. Too often, the innovator must choose between pursuing their idea and staying competitive for promotion. Innovation tours, fellowships, and rotational billets should be seen as accelerants for leadership, not liabilities. This shift requires cultural change, but it is a necessary one.

In The End: Innovation Is the Mission

None of this is easy. Innovation within a massive, bureaucratic institution will always encounter resistance. But the Air Force cannot afford to confuse slogans with systems. To innovate meaningfully, it must move beyond buzzwords and build the structures that allow both ideas and innovators to thrive.

The Gartner Hype Cycle teaches us that disillusionment is not failure—it is a phase. But it is also a choice. We can remain trapped in the trough, or we can build our way out.

If the Air Force chooses the latter, it must invest not just in technologies, but in capability enablers—the people, processes, and platforms that make innovation repeatable. Because in the end, the question is not whether the service will face future disruptions. It is whether it will be ready to meet them with speed, discipline, and imagination.

Innovation is not a side project. It is the mission.