When I first took the job standing a new leadership department at the Air Command and Staff College, I knew I wanted to do more than just structure a syllabus or write a set of learning objectives. I wanted to build something with soul. Something that would help mid-career officers not just check boxes on their way to O-5, but actually reflect—seriously, playfully, intellectually—on what kind of leaders they were becoming.

So naturally, I went shopping for starships.

On my bookshelf—just behind my desk, quietly but deliberately arranged, sat a small model of the Millennium Falcon, both versions of the USS Enterprise (NCC-1701 and NCC-1701-D), and the Battlestar Galactica. Four ships. Four command chairs. Four radically different kinds of leaders. I wasn’t planning on making them a part of the curriculum—at least not explicitly. But I hoped the models might spark the occasional hallway conversation, or maybe even lead to a deeper discussion about the nature of leadership itself.

I imagined a major wandering into my office and casually remarking, “Kirk or Picard?” That would be my in. From there, maybe we’d talk about the differences between charismatic and ethical leadership, or the tensions between tactical initiative and strategic patience. Perhaps someone would ask why I included Han Solo—after all, he wasn’t technically a captain in any formal sense (I mean he WAS a pirate). But that’s the point. Solo is the perfect stand-in for the reluctant leader, the maverick who never wanted the responsibility, but finds himself drawn into the fight anyway. And Galactica’s Admiral Adama? He’s the tired but unbreakable center of gravity in a system under existential stress.

But the conversations I had imagined never really took off. Maybe it was a little too geeky for a room full of majors. Or maybe people just didn’t have the bandwidth for metaphor when they were juggling course loads, writing papers, and thinking about their next assignment. Still, I couldn’t shake the feeling that there was something important here—something about leadership that science fiction had been exploring for decades that we, in our highly structured, bureaucratic institutions, were still catching up to.

And so, this post…

The Maverick and the Mission: Han Solo and Adaptive Leadership

Han Solo isn’t the kind of person you’d select to lead a squadron—or any formal unit, for that matter. He’s allergic to hierarchy, hostile to bureaucracy, and deeply skeptical of authority. And yet, over time, we watch him evolve into one of the key figures of the Rebellion and later, the Republic and the Resistance. Why?

Because Han represents the kind of adaptive leader needed in environments of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA). He makes decisions quickly, based on instinct and context. He builds trust not through positional authority but through loyalty, humor, and personal courage. He doesn’t read the operating manual—he rewrites it.

If I were to draw a military analogy, Han would be the small team leader dropped behind enemy lines with limited guidance. He thrives when the mission is vague but the stakes are high. He’s the kind of leader who breaks the rules for the right reasons—and usually succeeds because of it, not in spite of it.

Of course, that style has limits. Han doesn’t scale well. He’s not going to lead a battalion, and he certainly won’t survive in a staff job. But in an era of mission command, gray warfare, and rapidly shifting environments, we need leaders like Han who can think beyond the structure—and who are willing to take personal risks when the situation demands it.

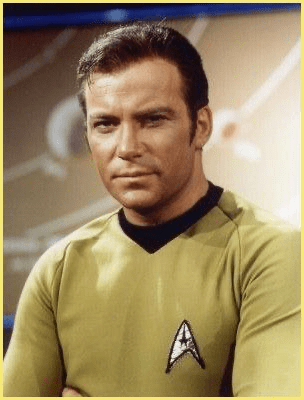

To Boldly Go: James T. Kirk and Strategic Risk-Taking

Captain James T. Kirk is, in many ways, the archetypal operational commander. Charismatic, daring, and emotionally attuned to his crew, Kirk walks the line between strategist and tactician with grace—and often, with swagger. He doesn’t just follow orders; he interprets them in the context of values and outcomes.

What makes Kirk so compelling as a leadership figure is his willingness to assume risk, not recklessly, but as a necessary element of command. He understands that leadership isn’t about following rules—it’s about using judgment in situations the rules never anticipated. In other words, Kirk operates at the edge of doctrine.

He represents the kind of leader who thrives in dynamic and contested environments, where the mission is evolving and the context changes faster than guidance can be updated. He sees the importance of the institution—but also its limitations. He respects loyalty, but he doesn’t confuse it with obedience. And when the mission demands bold action or principled dissent, he’s ready to act—even if it means going against the grain.

Kirk also models the tension between control and innovation. He trusts his team, but he often overrides them. He’s not perfect—but he is effective. And that opens up an important leadership conversation: What’s the cost of charisma? When does decisiveness become authoritarianism? And how do we teach risk without glamorizing recklessness?

The Weight of Command: William Adama and Servant Leadership in Crisis

If Kirk is the quintessential field general, then Admiral William Adama is the commander in crisis. In the reimagined Battlestar Galactica, Adama leads what is essentially the last remnants of humanity. The stakes are existential. The conditions are brutal. And the weight of command is overwhelming.

Adama doesn’t lead with flair. He leads with gravity. His leadership is deeply personal—rooted in responsibility, sacrifice, and moral authority. He doesn’t ask for loyalty; he earns it. He isn’t just a commander—he becomes the emotional and ethical anchor of the entire fleet.

Adama is a textbook case of servant leadership, not in the soft sense, but in the warrior sense. He makes decisions with an acute awareness of their human cost. He accepts loneliness as the price of command. And he puts the mission—and his people—before himself, even when it nearly destroys him.

What makes Adama’s leadership so resonant is not innovation, but endurance. He embodies the kind of leader who steps forward when everything else is falling apart. Not to create something new, but to preserve what matters most—integrity, cohesion, and purpose. He reminds us that in certain moments, leadership isn’t about shaping the future—it’s about keeping the present from disintegrating.

But this too raises valuable questions for leadership education: How do we prepare leaders for moral exhaustion? How do we support commanders who are breaking internally while holding the line externally? And how do we reconcile command authority with emotional transparency?

The Diplomat Philosopher: Jean-Luc Picard and Ethical Command in Complexity

Captain Jean-Luc Picard is a different breed altogether. He leads not through charisma or instinct, but through principled reasoning and intellectual depth. He is the embodiment of ethical leadership in complex systems—someone who believes that dialogue, reflection, and integrity are not just ideals, but operational necessities.

Picard doesn’t shoot first. He listens. He considers. He integrates. His command style reflects a commitment to systems thinking, cultural humility, and the long-term consequences of short-term choices.

Picard represents a kind of leadership that operates beyond immediate outcomes. His influence ripples through institutions, relationships, and moral frameworks. He’s the kind of leader who shapes not just missions, but cultures. Who teaches through presence, not performance. Whose authority stems from legitimacy, not position.

This kind of leadership is especially critical in environments where formal power is diffuse—where success depends on coalition-building, trust across boundaries, and deep alignment of values. But Picard is not without his limitations. In moments requiring speed, his deliberative style can appear slow. In high-tempo crises, his reliance on process can frustrate more action-oriented subordinates. And yet, in a world increasingly defined by complexity, ambiguity, and interconnected risk, Picard’s leadership may be more relevant than ever.

His presence invites reflection: Are we building leaders who can navigate complexity—or just manage complication?Are we cultivating ethical imagination—or just compliance? Are we teaching our officers to lead institutions—or merely to serve within them?

Bringing It Home: Leadership Lessons from SciFi Commanders

So what do these captains really offer us?

| Character | Primary Leadership Lens | Organizational Analogy | Key Tension |

| Han Solo | Adaptive Leadership | Informal leader in high-risk, low-structure ops | Legitimacy vs. Autonomy |

| James T. Kirk | Strategic/Complexity Leadership | Visionary military innovator pushing doctrine | Control vs. Innovation |

| William Adama | Servant + Systems Leadership | Institutional steward in existential crisis | Care vs. Paternalism |

| Jean-Luc Picard | Ethical + Complexity Leadership | Diplomatic leader in multinational setting | Reflection vs. Decisiveness |

They offer leadership archetypes, not as prescriptions, but as provocations. They remind us that leadership is not one-size-fits-all. That different contexts demand different strengths. That who we are—our temperament, our instincts, our values—shapes how we lead.

They also offer us a way to talk about leadership in a way that is less doctrinal and more human. Fiction gives us the freedom to explore tensions, contradictions, and growth without the pressure of career evaluation or real-world consequences. It creates a space for honest reflection, for imaginative empathy, for intellectual play.

In retrospect, maybe my starship models were too geeky for the office. Or maybe I just didn’t explain them well enough. But I still believe in the conversations they could have sparked.

Because whether you find yourself channeling Solo, Kirk, Adama, or Picard—or someone entirely different—the real question remains: What kind of leader are you becoming, and why?

And maybe that’s the conversation that matters most….