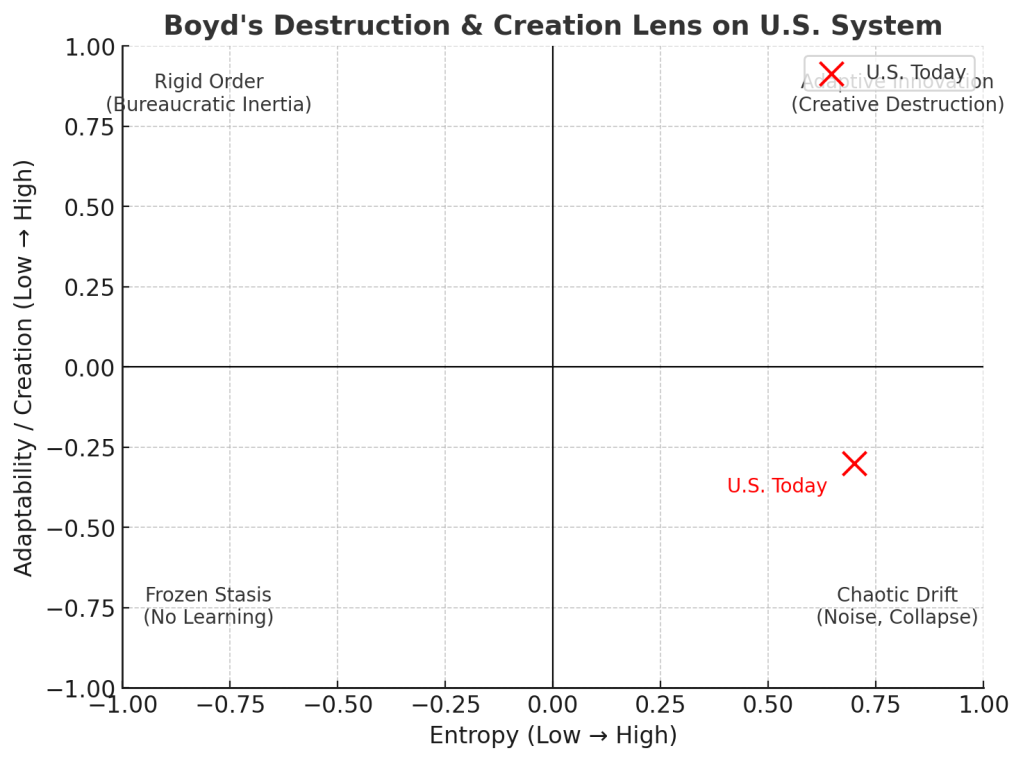

John Boyd’s Destruction and Creation is one of those slim essays that, once read, refuses to leave the bloodstream. Written in 1976, in the shadow of Vietnam and the twilight of American confidence, it is at once a meditation on cognition and a blueprint for strategy. Boyd insists that orientation—our ability to interpret and act in a changing environment—requires both destruction and creation. We must constantly tear down old concepts, dissolve brittle structures, and then reassemble fragments into new patterns that better match reality. Without this oscillation, we collapse into either frozen rigidity or incoherent chaos.

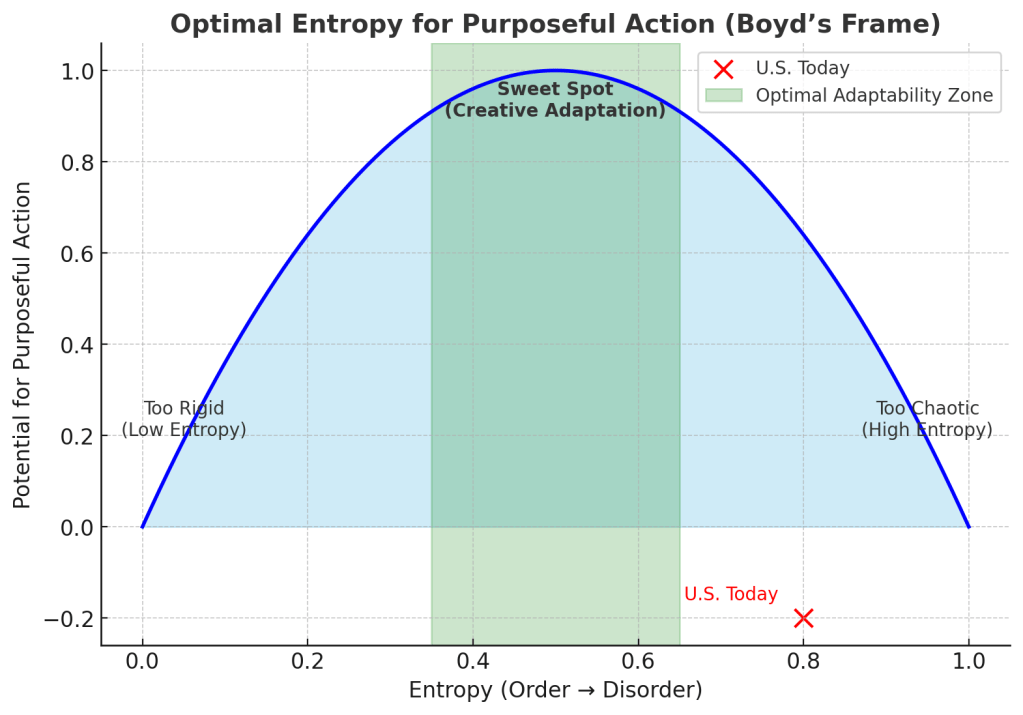

Boyd borrowed heavily from physics and mathematics, drawing on Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, and the second law of thermodynamics. He argued that all human systems move toward entropy, toward disorder and uncertainty. A strategist’s task is not to eliminate entropy (an impossibility), but to ride its currents. We must learn to generate just enough disorder to break apart the obsolete, while simultaneously building coherence to act in the moment.

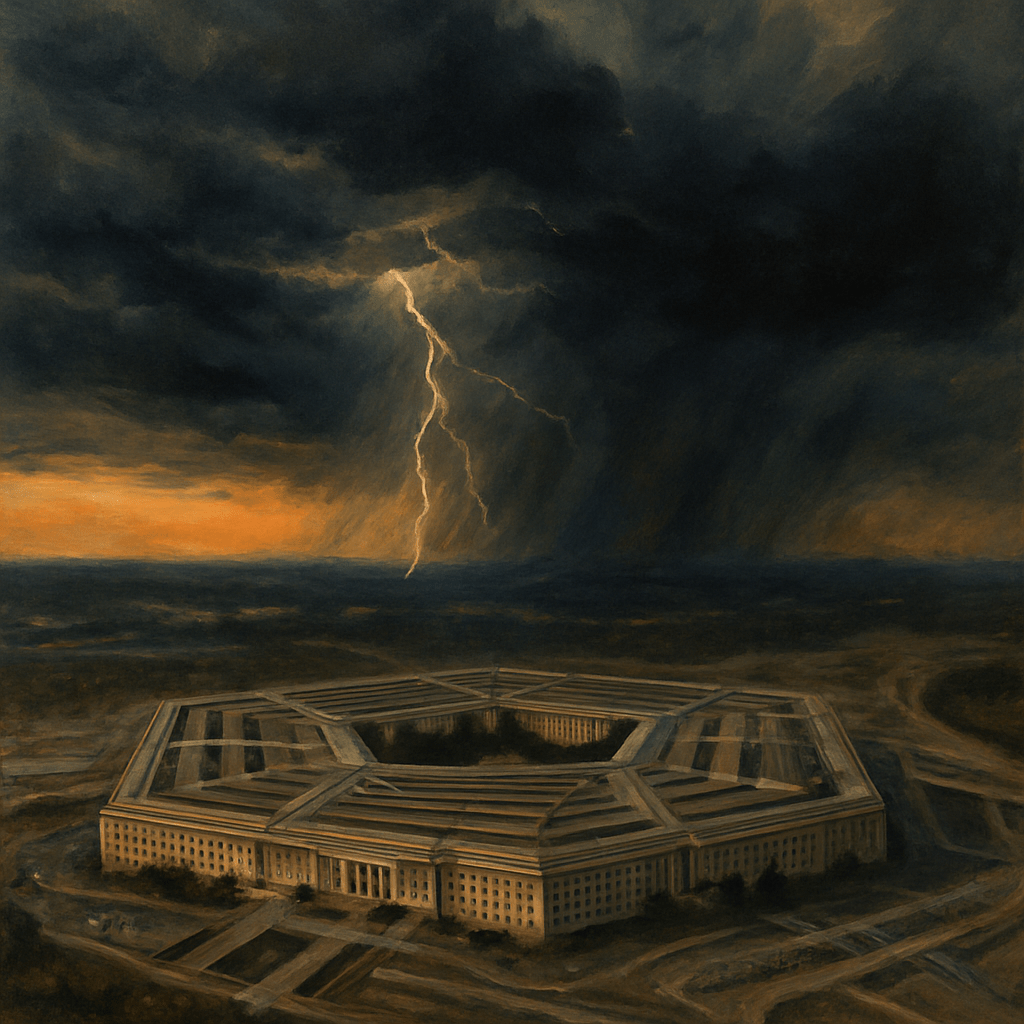

Measured by Boyd’s framework, the United States Department of Defense now known by many as the Department of War—the title restored by executive order in September 2025—finds itself in a dangerous position. It sits neither in the stable order of low entropy nor in the creative churn of productive destruction. Instead, it drifts in the far right of the curve: high entropy, high noise, low ability to extract useful work.

Entropy in the System

Entropy in physics is the measure of disorder, the degree to which energy is dispersed and no longer available to perform work. In Boyd’s usage, entropy is a metaphor for confusion, contradiction, and incoherence. High entropy means the system cannot orient. Low entropy, on the other hand, can mean rigid stasis—predictable but unable to adapt.

The U.S. national security system today embodies both extremes at once. Its bureaucratic core remains ossified: slow, process-driven, locked in legacy structures designed for twentieth-century industrial war. Simultaneously, its political environment injects chaos: sudden firings, unexpected retirements of senior commanders, unpredictable budgetary cliffs, government shutdowns, and public fights over fitness standards while strategic focus drifts. It is as though the heart of the machine is frozen, while the head flails wildly.

This combination does not yield balance. It yields drift.

Ukraine: A Testing Ground for Entropy

Ukraine is often described as a laboratory of modern war, a place where drones, electronic warfare, and attritable mass are rewriting doctrine in real time. For the United States, Ukraine is also a mirror of entropy. Washington sends aid in fits and starts, hostage to political dysfunction. Allies watch the internal churn in Congress and wonder if U.S. commitments will hold. Meanwhile, the Department of War struggles to adapt its own concepts to lessons from the field: the rapid innovation cycles of Ukrainian units clash with the Pentagon’s plodding procurement bureaucracy.

Boyd would recognize the problem immediately. Our destruction cycles are partial, we see what is breaking down in Ukraine, but our creation cycles are stunted. We fail to rebuild doctrine or acquisition structures fast enough to match the entropy of the battlefield. We observe and orient, but our decision and action lags behind.

Venezuela and the Caribbean Gambit

In recent months, the deployment of the USS Gerald R. Ford strike group to the Caribbean in response to Venezuelan tensions illustrates another entropy trap. The move appears less as a coherent strategy than as a signaling gesture—destruction without creation. Russia masses near Norway; we deploy a carrier near Venezuela. Are these moves linked? Are they bargaining chips in a geopolitical game? Or are they reactive spasms, disconnected fragments of policy?

Boyd would warn that such actions, absent coherent orientation, increase entropy. They generate noise without building patterns. They disperse energy that cannot be harnessed for long-term work.

Gaza: Fragmented Strategy and the Crisis of Orientation

The war in Gaza exposes another fault line. The U.S. attempts to reassure allies, deter adversaries, and manage domestic political fractures all at once. The result is a cacophony of messages: unconditional support for Israel on one hand, quiet warnings about proportionality on the other; calls for humanitarian restraint alongside shipments of advanced munitions.

This is high entropy in Boyd’s sense. Observations flood the system, but they do not cohere into a stable orientation. Decision makers oscillate between competing narratives. Actions are inconsistent, undermining credibility. Entropy rises; the ability to perform purposeful strategic work declines.

Internal Churn: Firings, Retirements, and the Loss of Continuity

Inside the Department of War, entropy manifests in the churn of leadership. High-profile firings, abrupt retirements of Joint Staff officers, and the exodus of experienced commanders destabilize the institution’s orientation. Continuity, the slow accretion of wisdom through careers of service, erodes.

At the same time, attention shifts away from strategy to internal debates—fitness standards, diversity metrics, or bureaucratic re-orgs. These are not trivial, but when they dominate the strategic agenda, they signal entropy’s victory. The institution is trapped in destruction—tearing down standards, reshaping metrics—without corresponding creation in the form of a clarified strategic vision.

Shutdowns and Pay Freezes: Entropy at the Core

Perhaps nothing illustrates Boyd’s entropy metaphor more vividly than the recurring government shutdowns. When Congress fails to pass budgets, military members go unpaid, families are left uncertain, and readiness erodes. Energy exists—the vast resources of the U.S. government—but it cannot be harnessed to do work. It is entropy made manifest: a diffusion of potential that produces no effect.

Boyd would remind us that orientation is built on trust and patterns. A military that cannot trust its paychecks is a military in disorientation. High entropy corrodes morale as surely as it corrodes doctrine.

The Fitness Paradox: Strategy Lost in Translation

Recent focus from senior leadership on physical fitness standards offers another case. Readiness is essential. But when fitness becomes a proxy for strategy… when bureaucratic energy flows into measuring waistlines while wars rage abroad…the system misorients. It confuses inputs for outputs.

Boyd might call this entropy through misallocation. The energy of the institution is not gone, but it is spread thinly across trivial pursuits rather than concentrated on adaptation to adversary innovation. This too lowers the system’s capacity to generate useful work.

The Department of War and the Drift of Strategy

In September 2025, President Trump signed an executive order “restoring” the Department of War, renaming the Secretary of Defense as the Secretary of War. The language is deliberate: a rejection of the managerial euphemism “defense” in favor of blunt clarity. To its proponents, the move signals seriousness and resolve. To its critics, it stirs ghosts of militarism and muddled legality.

Yet the shift only underscores Boyd’s warning. A department that renames itself for “war” still struggles to orient strategically. The rebranding does not by itself destroy obsolete concepts or create new ones. Instead, it highlights the gap between rhetoric and reality: the institution called to fight wars is simultaneously consumed by shutdowns, pay freezes, internal churn, and debates over fitness standards. Allies and adversaries alike see the semiotic dissonance: a Department of War that cannot fully decide what war it is preparing for.

Boyd might argue that this very contradiction is entropy made flesh—two names, two missions, two realities in collision. It is destruction without creation, noise without coherence. The Department of War, reborn in name, remains adrift in practice.

Toward Creative Entropy

Where then should the Department aim? Boyd’s curve suggests a middle zone: not the frozen order of low entropy, nor the chaotic drift of high entropy, but the dynamic balance of creative adaptation.

- In Ukraine, this would mean not only supplying aid but restructuring doctrine and procurement to absorb lessons in attritable mass and drone warfare.

- In Venezuela, it would mean linking deployments to a coherent strategic narrative, rather than reactive signaling.

- In Gaza, it would mean clarifying U.S. red lines and moral commitments, reducing contradictory signals that feed entropy.

- Internally, it would mean stabilizing leadership, prioritizing strategic clarity over bureaucratic debates, and ensuring that shutdowns and pay freezes never again undermine orientation.

The task is immense. But Boyd reminds us that all human understanding is a process of destruction and creation. Entropy will rise; our task is to harness it, not deny it.

Conclusion: Boyd’s Warning

If Boyd could look at today’s Department of War, he might offer a grim assessment. The system is awash in entropy. Destruction races ahead of creation. Orientation falters. The result is drift—a great machine full of energy but unable to perform useful work.

Yet Boyd would also insist that orientation can be regained. Through genuine destruction of obsolete concepts and deliberate creation of new patterns, the Department could move back toward the zone of creative entropy—where disorder fuels adaptation rather than collapse.

The alternative is to remain where we are: in the heat death of strategy, a Department of War that no longer wages war, but manages its own entropy.