There is something unsettling, even dangerous, about the iconoclast. From the origin of the word itself—a compound of the Greek eikōn, meaning “image,” and klan, “to break”—the iconoclast has always been defined in opposition to sacred norms. In its earliest usage, the term described those who quite literally smashed religious images during the Byzantine Iconoclasm of the eighth and ninth centuries. But the image-breaker is not merely a relic of ancient heresy. In the realm of strategy and leadership, the iconoclast remains a deeply relevant figure, one who does not simply rebel or criticize but goes further: undermining foundational assumptions and often reimagining the structures that hold power.

In modern usage, iconoclasts are often confused with rebels or critics. A rebel may oppose convention out of defiance or ideology. A critic may point out flaws but still operate within the same frame. The iconoclast, however, seeks to dismantle that frame entirely. Where the rebel disrupts, the iconoclast deconstructs. Where the critic comments, the iconoclast carves space for new creation. Nietzsche captured this impulse best when he described his philosophy as “a revaluation of all values” and envisioned the philosopher as one who “philosophizes with a hammer” —not to blindly destroy, but to tap, test, and reveal which of our cherished idols are hollow.

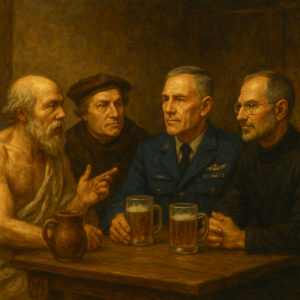

Such figures are rare, and rarely comfortable to be around. But history makes clear that they are indispensable, especially in moments of institutional entropy. Socrates questioned the moral and political assumptions of Athenian democracy with such persistence that his society deemed him a threat to civic stability. He never claimed to possess truth, only to interrogate it. His dialectic stripped away pretense, revealing how little even the most powerful citizens understood the very virtues they professed. For this, he was condemned. Yet his legacy became foundational to Western philosophy, precisely because he dared to ask questions others feared to pose.

Martin Luther likewise shattered idols—not images, but theological and institutional dogmas. When he nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the church door at Wittenberg in 1517, he launched not only the Protestant Reformation but a wholesale rethinking of authority itself. Luther’s genius lay not in rebellion alone, but in his strategic clarity: identifying where the edifice of the Church had ossified and offering an alternative rooted in scripture, conscience, and a direct relationship to the divine. His actions exposed the cracks in an institution that had claimed divine infallibility and, by doing so, set off centuries of transformation in religion, politics, and education.

In the realm of military strategy, Colonel John Boyd offers a more contemporary model. As a maverick Air Force fighter pilot and theorist, Boyd not only challenged the prevailing doctrines of his service but rewrote the rules of warfighting itself. His “OODA loop” (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) became a foundational concept in maneuver warfare, emphasizing agility and adaptability over rigid planning. Boyd dismantled hierarchical conceptions of airpower and pushed for reforms that often ran afoul of institutional comfort. His legacy endures not because he was always right, but because he asked the right questions at the right time, refusing to accept dogma when it hindered operational effectiveness.

Yet if iconoclasm is to be meaningful, it must not only destroy; it must also create. This is the difference between the provocateur and the strategist. In the modern business world, few figures illustrate this tension more clearly than Steve Jobs. Unlike Elon Musk, whose disruptive approach often veers toward spectacle and volatility, Jobs’ iconoclasm was ultimately rooted in discipline, design, and deeply held convictions about user experience and technological elegance. Jobs did not merely break things to demonstrate his power or defy consensus. He stripped products and companies down to their essence to reorient them toward clarity and purpose.

When Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, the company was on the brink of collapse. Its product line was bloated, its vision muddled. Jobs slashed the catalog, focused on a handful of core offerings, and infused the organization with a new aesthetic and philosophical rigor. The result was not just a turnaround but a renaissance. The iMac, the iPod, and eventually the iPhone were not just commercial successes; they were strategic recalibrations. Jobs’ genius was to see that innovation was not simply a matter of adding more, but of removing the unnecessary—breaking the habits and assumptions that led to clutter and confusion.

Musk, by contrast, often embodies the chaos of the iconoclast untethered. While his ventures have produced undeniable breakthroughs in space exploration and electric vehicles, his leadership frequently courts dysfunction. His approach suggests a destructiveness that is not always followed by clarity or coherence.

Where Jobs pursued perfection, Musk sometimes seems content with provocation. This is not to deny Musk’s contributions, but to draw a crucial distinction: the iconoclast as strategist versus the iconoclast as spectacle.

The institutional world—especially the military—does not easily accommodate iconoclasts. Hierarchies, doctrines, and traditions resist disruption by design. Yet in times of accelerated change, rigid structures become brittle. Doctrine ossifies. Systems stagnate. The leader who can channel the spirit of Socrates, Luther, Boyd, or Jobs becomes not a threat, but a necessity. Such leaders break to rebuild, not to burn. They see what is sacred, test it, and are willing to let it fall if it no longer serves.

For strategic leaders today, the lesson is not to become iconoclasts for their own sake, but to develop the discernment to know when iconoclasm is called for. The hammer must be wielded with care. Not every idol is false; not every tradition is a shackle. But when vision is clouded by ritual, when performance is hindered by sacred cows, and when systems reward obedience over insight, then image-breaking becomes an ethical imperative.

This is not a call to abandon institutions, but to save them. The true iconoclast loves the potential of the institution too much to let it decay unnoticed. They disturb the peace not because they hate order, but because they see a better order waiting to be born. In that sense, the strategist with a hammer is not an anarchist. He or she is a reformer, a builder, a visionary in the most demanding sense of the word.

Leadership, then, is not simply about stewarding what is, but courageously clearing space for what might be. And in that space, if we listen closely, we may hear the faint ring of a hammer against an idol—not to desecrate, but to discern, to test, and, ultimately, to transform.