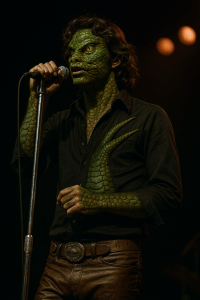

“I am the Lizard King. I can do anything.” — Jim Morrison

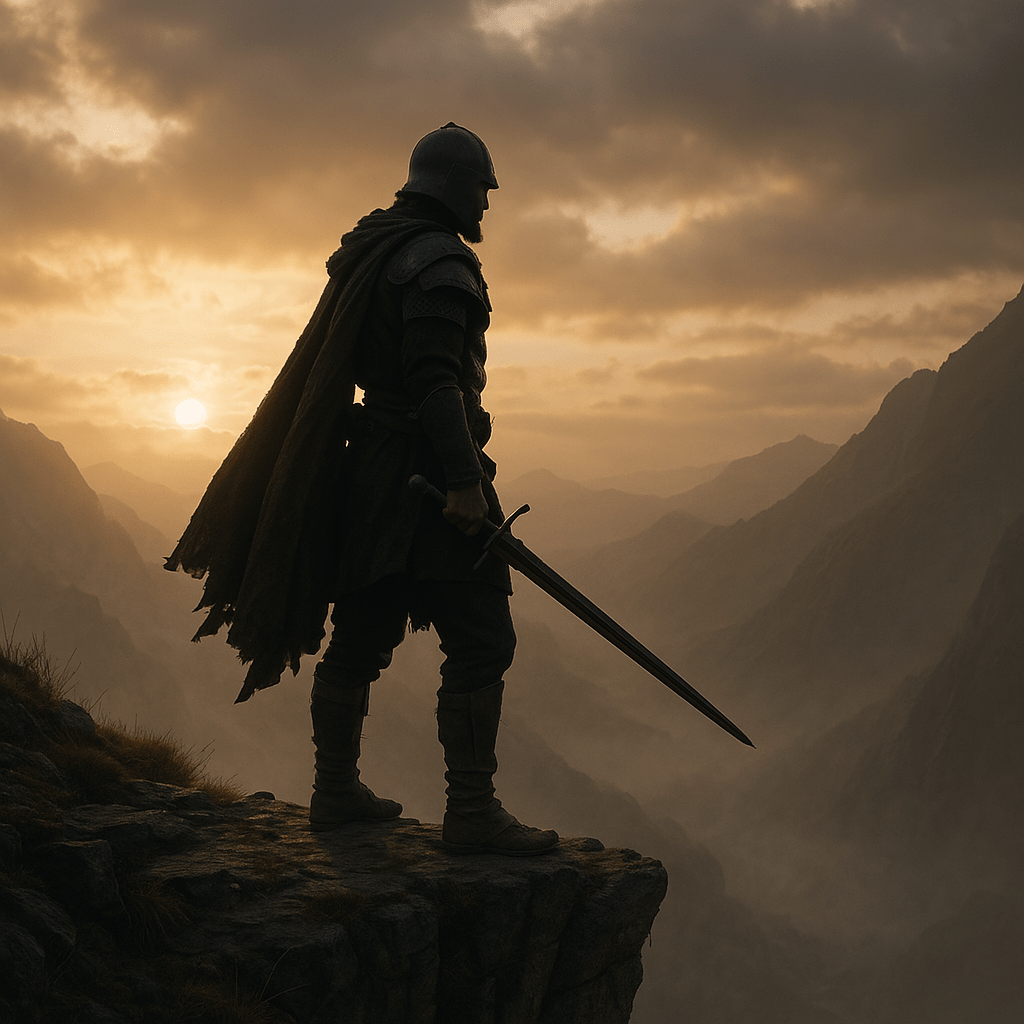

Jim Morrison was not a conventional leader. He was a poet-shaman, a provocateur, and a performer who unraveled boundaries rather than enforcing them. But in an age defined by complexity, ambiguity, and accelerating change, Morrison’s self-styled persona—the Lizard King—offers more than artistic flair. It becomes a powerful metaphor for a type of leadership that is increasingly vital today: a leadership that emerges from the margins, moves through myth, and leads with imagination and identity.

In his 1968 poetry collection The Lords and The New Creatures, Morrison first gave literary birth to the Lizard King persona. The book itself is part surrealist meditation, part cinematic critique, and part mythopoetic journey through the subconscious. Across fragmented verses and haunting aphorisms, Morrison lays out a theory of perception, power, and resistance. The Lizard King becomes not just a poetic alias, but an edgewalker archetype—someone who dares to cross the threshold from the structured world of the known into the unpredictable world of transformation.

It seems as if that archetype—refined and reinterpreted—resonates with contemporary leadership practice, particularly in contexts where identity, disruption, and strategy intersect.

1. The Leader as Disruptor-Philosopher

In contrast to leaders shaped by institutional processes and traditional hierarchies, Morrison’s Lizard King emerges as a disruptor-philosopher—a figure who sees systems not as permanent structures, but as temporary illusions. The phrase “I can do anything” may sound like ego, but it reflects a deeper conviction: the belief that agency is something we must claim, not inherit.

This is leadership not based on positional power, but on existential clarity. In strategic environments—military, academic, or organizational—there is a growing recognition that innovation and transformation do not emerge from control alone. They arise from creative tension, moral courage, and the ability to dwell in liminal, edge-spanning roles. In short: they arise from edgewalkers.

2. Authenticity as Strategic Currency

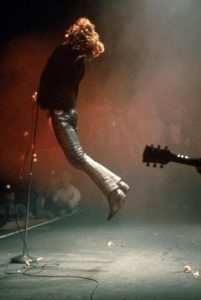

Morrison’s greatest act of strategy wasn’t a speech, a plan, or a protest. It was radical self-expression. He refused to be assimilated into the cultural or corporate machinery of his time—and in that refusal, he modeled something increasingly understood in leadership development today: that authenticity is not a luxury—it is strategic currency.

Edgewalkers often operate on the borderlands of tradition and transformation. They’re not interested in being different for its own sake—they simply cannot function in environments that demand a denial of self. Morrison’s example shows how dangerous—and how necessary—it can be to lead with who you are, rather than what you’re told to be.

3. Myth and Meaning in Strategic Culture

Leadership divorced from story becomes mechanistic. Strategy, in the absence of narrative, reduces to logistics. Morrison understood this deeply. The creation of the Lizard King was not vanity—it was mythmaking. It gave form to chaos and allowed Morrison to act within an identity large enough to hold contradiction, intensity, and transformation.

Modern leaders must also be mythmakers—not in the sense of deception, but in the sense of shaping meaningful frameworks through which teams, organizations, and societies understand themselves. This is the work of the edgewalker—not to escape systems, but to offer new ways of seeing them.

4. Innovation and the Strategic Self

Morrison’s life offers a cautionary tale. His collapsing of identity and performance eventually became unsustainable. But his insight remains critical: innovation begins at the level of selfhood. No strategic model can succeed in the absence of clarity around who the leader is—and what they are becoming.

Edgewalkers are often the first to sense that transformation must happen within before it can scale outward. They instinctively resist the separation of identity and strategy—and in that resistance, they often spark the conditions for change.

5. From Firestarter to Firekeeper

Morrison ignited something—but he could not contain it. His flame consumed him. He lacked the infrastructure, mentorship, and discipline to sustain insight and steward transformation. His archetype is vital—but incomplete.

If the Lizard King is the firestarter, modern leadership must also cultivate the firekeeper—the one who tends the flame over time, protects it, shares it, and builds systems around it without extinguishing its power.

Edgewalkers, when guided and supported, often become translators between innovation and institution—between myth and mission. This is where the real alchemy happens.

6. Call to Action: Leading from the Edge

The Lizard King isn’t just an artifact of a psychedelic past. He’s a symbol of a strategic future—one that values story, identity, disruption, and the wisdom to dance at the edge of systems. In times of complexity, where control is fragile and meaning is contested, leadership must be reimagined not as management, but as myth-guided movement.

Edgewalkers already live in this space. The task now is to recognize them, empower them, and learn from them—not to tame their energy, but to shape systems strong enough to hold their fire.

Jim Morrison never wrote doctrine, but he performed transformation. His poetry, persona, and myth remind us that the most dangerous leaders are sometimes the most necessary ones—and that real leadership begins not with plans, but with the courage to stand at the threshold, between what is and what must come next.

To lead from the edge is not to reject the center.

It is to renew it—from the outside in.