The paradox is as old as artistry itself: groups that are forged in the fires of struggle often dissolve in the warmth of success. This truth spans domains—from military units to start-ups, from revolutionary movements to legendary rock bands. The tighter the early fight, the stronger the bond. But when the fight is over, cohesion wanes. This phenomenon isn’t just anecdotal—it has theoretical roots in sociology, psychology, and organizational science. And nowhere is it more poignantly illustrated than in the history of iconic rock bands.

Consider the scrappy ascent of bands like Pink Floyd, The Police, or Oasis. These groups started as underdogs, unknown and underfunded, fighting for their artistic voice and a place on the charts. The shared adversity created a singular focus and deep camaraderie. But as their fame grew, so did ego, ambition, and dissonance. The story of many bands follows a recognizable arc: struggle, success, fragmentation.

The Struggle: Where Cohesion is Born

Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner) posits that our sense of self becomes deeply tied to group identity, especially under external pressure. Similarly, Group Cohesion Theory (Festinger) shows that teams under threat or pressure display higher unity. For bands, early touring years—traveling in cramped vans, playing to empty bars, sleeping on couches—aren’t just logistical nightmares. They’re crucibles.

Bands like Soundgarden, R.E.M., and Dire Straits all began in obscurity, sharpening their sound through countless gigs and small-time recording sessions. The hardship wasn’t incidental; it was formative. These were the years of shared suffering and creative experimentation—where “us against the world” wasn’t just a sentiment but a survival strategy.

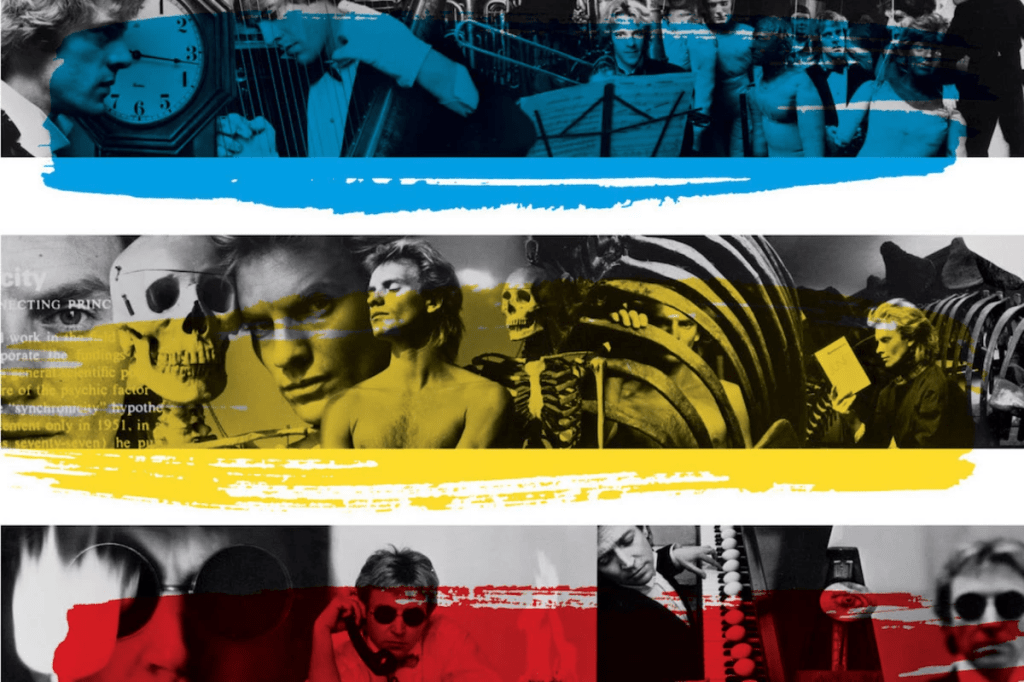

The Police, for instance, became globally dominant after Synchronicity (1983), which featured mega-hits like “Every Breath You Take.” But by 1986, the band disbanded. The very pressures of fame that had validated their early struggle now dismantled their unity.

Success: The Double-Edged Sword

Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan) helps explain the shift. Intrinsic motivations—love of music, creative expression—can become corrupted when extrinsic rewards like fame, money, and status take center stage. This often leads to misalignment of purpose within the group.

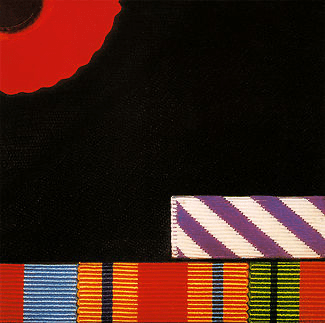

Take Pink Floyd. The band’s creative apex—The Dark Side of the Moon (1973), Wish You Were Here (1975), and The Wall (1979)—was followed by a slow fracture. Roger Waters and David Gilmour clashed over artistic direction, culminating in Waters calling the band a “spent force” and leaving in 1985. Despite continuing under Gilmour’s lead, the spirit of Pink Floyd as a unified creative entity had disintegrated.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs also offers insight. Once basic needs (security, belonging) are met, individuals seek self-actualization. In bands, this often means solo projects, new creative ventures, or demands for greater control—driving a wedge between members.

Rob Thomas of Matchbox Twenty exemplifies this. After the explosive success of Yourself or Someone Like You (1996) and Mad Season (2000), Thomas’s solo career became a focal point, shifting energy away from the band. Though Matchbox Twenty never officially broke up, their cohesion dissolved into occasional reunions.

The Fracture: Ego, Power, and Creative Divergence

The group development model by Bruce Tuckman—Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing, Adjourning—aptly describes band trajectories. The “storming” phase often returns after success, when previously latent power dynamics surface. Creative control, songwriting credits, tour decisions—all become battlegrounds.

Oasis perhaps dramatizes this best. (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? (1995) catapulted them to global stardom. But the Gallagher brothers’ legendary feuding—fueled by conflicting visions and egos—led to their 2009 split. Internal tension eroded what external challenge had once fortified.

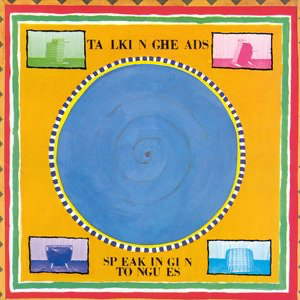

The same pattern is seen in Talking Heads. Despite groundbreaking albums like Remain in Light and Speaking in Tongues, David Byrne’s growing dominance and solo interests created rifts. By 1991, they informally disbanded, ending a pioneering run in art-rock.

Game Theory helps illuminate the internal logic. As personal rewards begin to outweigh collective benefits, cooperative behavior diminishes. Members face a kind of Prisoner’s Dilemma: stay and risk stagnation, or defect and pursue personal gain.

Case Studies: From Cohesion to Collapse

The White Stripes: With Elephant (2003) and “Seven Nation Army,” Jack and Meg White reached artistic and commercial heights. But by 2011, they called it quits, citing “a myriad of reasons.” Minimalist by nature, the band’s duality was its strength—and ultimately its limitation.

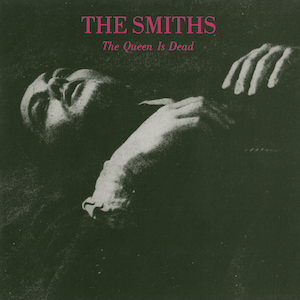

The Smiths: Critical darlings with The Queen Is Dead (1986), they never achieved full global dominance. Yet creative friction, particularly between Morrissey and Marr, led to a 1987 breakup—just as mainstream success seemed inevitable.

The Verve: Urban Hymns (1997) and its anthemic “Bitter Sweet Symphony” defined an era. But internal instability—amplified by rapid fame—led to multiple breakups, culminating in a permanent disbanding in 2009.

Creedence Clearwater Revival: Despite dominating the late ’60s with hits like “Bad Moon Rising,” CCR disbanded in 1972, torn apart by personal disputes and leadership struggles.

The Exception: The Rolling Stones

The Stones are a rare case—an adaptive organism rather than a combustible collective. Why did they endure when so many others perished?

- Stable but Evolving Leadership: Jagger and Richards managed to maintain creative friction without irreparable rupture. Their conflicts became productive tension rather than terminal fracture.

- Clear Roles: Members had distinct identities and lanes. Jagger was the frontman and strategist; Richards the musical anchor. Supporting players (Watts, Wyman, Wood) added depth without threatening cohesion.

- Strategic Reinvention: The band evolved from blues to psychedelia, arena rock, disco, and pop, embodying the principles of Resilience Theory. They survived by adapting.

- Cultural and Economic Incentives: As cultural icons, the Stones found a new business model: legacy touring, licensing, merchandising. Breaking up would have been irrational from both a brand and revenue perspective.

Still, they weren’t immune. Brian Jones’s death, Richards’ drug issues, and a near-collapse in the 1980s tested their bond. But unlike their peers, they transformed pressure into longevity.

Broader Implications: Teams, Startups, and Nations

The band dynamic reflects a broader truth in organizational life. Startups, like bands, often thrive on struggle—shared goals, bootstrapped missions, and anti-establishment energy. But as success arrives, priorities diversify. Founders disagree, missions drift, early cohesion fades.

Nations, too, follow this cycle. Glubb Pasha’s “Fate of Empires” posits that civilizations rise through struggle and fall through decadence. The early unity of purpose gives way to internal division and moral exhaustion.

Conclusion: Struggle is the Glue, Success the Solvent

In the end, success is not the enemy, but it is the test. For bands—and any group—the challenge is not just to rise but to remain. The story of great music is often the story of great collapse. But it is in that very collapse that we find the deeper narrative: that cohesion is forged in fire, not comfort.

Understanding this dynamic offers lessons not just for rock bands, but for teams, leaders, and organizations navigating the treacherous terrain between aspiration and achievement.

To succeed is one thing. To survive success is another.