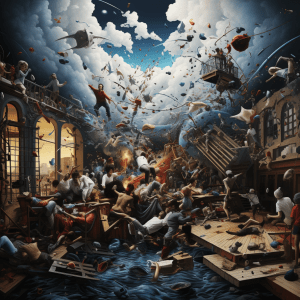

Innovation in structured organizations like the military is a complex interplay between order and chaos. While the hierarchical, disciplined nature of such organizations leans heavily towards order, the very essence of innovation is often found in chaos—those unplanned moments of creativity, the unpredictable intermingling of diverse ideas, and the willingness to challenge established norms. Navigating this delicate balance is crucial for leaders who aim to foster a culture of innovation without compromising the integrity of the organization’s structure.

Understanding the dichotomy between order and chaos in innovation calls for intellectual frameworks that can guide leaders through this challenging landscape. The theories of Hans-Georg Gadamer and Carl Rogers, although originating from different disciplines, offer valuable insights in this context. Gadamer’s hermeneutical principles bring the needed structure and order, grounding innovation in tradition, authority, and systematic reflection. On the other hand, Rogers’ person-centered theory introduces the element of chaos, emphasizing the significance of individual creativity, personal growth, and emotional intelligence in bringing about innovative changes.

By reconciling Gadamer’s ordered perspective with Rogers’ more chaotic view, leaders can cultivate an environment that not only tolerates but thrives on the creative tension between order and chaos. This balanced approach could be the key to unlocking sustainable, impactful innovation, even within the stringent frameworks of highly structured organizations like the military.

WHAT’S A HARD STRUCTURE:

In my dissertation, I grappled with the complex challenge of fostering innovation within the rigid confines of a hard structure. The central question revolved around how leaders can skillfully navigate between the poles of order and chaos. This issue extends to self-awareness: it’s critical for leaders to introspect and recognize their own inclinations. Do they naturally gravitate towards order, favoring rules and structure? Or do they lean into chaos, valuing flexibility and spontaneity? Understanding one’s own tendencies is a pivotal step in effectively balancing these opposing forces to enable meaningful innovation.

Hard Structures

- Hierarchical Rigidity: In hard structures, there is often a clearly defined, non-negotiable chain of command. Decisions usually flow from the top down with little room for deviation.

- Strict Regulations and Procedures: These organizations operate under a set of firm rules and standard operating procedures that allow for minimal flexibility.

- Limited Autonomy: Employees or members in hard structures have less freedom to make independent decisions and are usually bound by a strict code of conduct.

- Inflexibility: Hard structures are often resistant to change and slow to adapt to new methodologies or shifts in organizational strategy.

- Examples: The military, law enforcement agencies, and certain types of manufacturing setups can be considered hard structures due to their stringent rules and highly regulated environments.

Gadamer and Rogers

The theories of Hans-Georg Gadamer and Carl Rogers come from different intellectual traditions—Gadamer from the field of hermeneutics and philosophy, and Rogers from humanistic psychology. However, both can offer valuable insights when applied to the area of innovation, particularly within leadership and organizational settings. Here’s a comparison focusing on Gadamer’s four pillars and Rogers’ nineteen propositions:

Gadamer’s Four Pillars and Innovation

- Understanding Own Prejudice Towards Ideas: Leaders must be aware of their own biases and preconceived notions that might hinder the innovative process. This self-awareness can open up new pathways for creativity and novel solutions.

- Acknowledging Tradition: According to Gadamer, every situation is deeply rooted in historical and social contexts. For innovation to be effective, leaders should understand and appreciate the traditions and established practices that shape their field or organization.

- Recognizing Authority: In any organizational setting, there are figures of authority whose opinions are highly valued. Recognizing this can help leaders navigate the complexities of introducing innovations effectively.

- Engaging in Reflection: Gadamer advocates for the constant dialogue and interpretation of experiences. In the context of innovation, this means that leaders should continually reassess and refine their strategies and approaches.

Carl Rogers’ Nineteen Propositions and Innovation

- Self-Concept: Rogers’ propositions place a strong emphasis on the importance of self-concept. In an innovative setting, leaders should help team members understand their value and capabilities.

- Genuineness, Acceptance, and Empathy: For Rogers, these are vital for any interpersonal relationship. Leaders can foster an innovative environment by being genuine, accepting, and empathetic.

- Organismic Valuing Process: This refers to an individual’s innate capability to strive for improvement. In innovation, this can be seen as the constant drive to innovate and improve.

- Conditional and Unconditional Positive Regard: Rogers discusses the effects of conditions of worth imposed by society. Leaders should aim for unconditional positive regard to stimulate creativity.

- Congruence: This means that one’s self-image should closely match their actual experiences. Leaders should strive for congruence to maintain integrity and trust, which are crucial for innovation.

Comparison

- Self-Awareness: Both theories highlight the importance of self-awareness, although from different angles—Gadamer focuses on understanding one’s prejudices, while Rogers emphasizes self-concept and congruence.

- Context and Tradition: Gadamer explicitly mentions the need to acknowledge tradition and authority. While Rogers doesn’t directly speak to this, his emphasis on societal conditions of worth can be viewed as an implicit acknowledgment of the role of tradition and authority.

- Interpersonal Relationships: Rogers places considerable emphasis on interpersonal dynamics, such as genuineness, acceptance, and empathy, which can be crucial in a team-driven innovative process. Gadamer’s idea of engaging in reflection can include dialogical reflection, which also involves interpersonal dynamics.

- Continuous Improvement: Both theories, albeit differently, emphasize the need for ongoing assessment—Gadamer through reflection and Rogers through the organismic valuing process.

By applying these insights from Gadamer and Rogers, leaders in innovation can develop a more holistic, nuanced approach that respects both individual potential and the complexity of historical and social contexts.

Yin and Yang

The concepts of Yin and Yang originate from ancient Chinese philosophy and cosmology, representing the dualistic nature of existence where opposite forces are interconnected and interdependent. Applying the concept of Yin and Yang to the theories of Carl Rogers and Hans-Georg Gadamer can offer a unique lens through which to understand their contributions, particularly in the context of innovation and leadership.

Carl Rogers as Yin

- Inward Focus: Rogers’ emphasis on self-concept, personal growth, and individual experience aligns with the Yin characteristics of inwardness and subjectivity.

- Nurturing Environment: The emphasis Rogers places on empathy, unconditional positive regard, and acceptance resembles the nurturing, sustaining qualities associated with Yin.

- Personal Authenticity: Rogers’ focus on genuineness and congruence speaks to the authenticity often associated with the Yin aspect.

- Emotional Intelligence: Rogers stresses the importance of emotional understanding and self-acceptance, qualities that can be seen as reflective, and therefore, Yin in nature.

Hans-Georg Gadamer as Yang

- External Context: Gadamer’s emphasis on tradition and authority aligns well with the outward, structural focus typically associated with Yang.

- Objective Reality: Gadamer’s hermeneutics often concern interpreting texts and traditions that exist independent of the individual, a perspective that could be seen as more objective and thus, Yang-oriented.

- Active Engagement: The idea of engaging in reflection and interpretation implies an active relationship with the world, resonating with the active, dynamic qualities of Yang.

- Logical Analysis: Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics often involve intricate logical reasoning, a characteristic that could be viewed as more aligned with the analytical aspects of Yang.

Application to Innovation and Leadership

- Balanced Approach: A leader might integrate Rogers’ person-centered approach to nurture creativity and emotional intelligence within teams (Yin), while using Gadamer’s pillars to understand and navigate organizational traditions and authority (Yang).

- Dynamic Interplay: The Yin of Rogers can help in the initial stages of ideation, promoting a safe space for creativity. The Yang of Gadamer can be vital in the later stages where an idea needs to be concretized and aligned with organizational objectives.

- Harmony: Both perspectives can exist in harmony, offering a balanced approach to innovation. The inward focus of Rogers’ theories (Yin) complements the outward focus of Gadamer’s (Yang), creating a holistic strategy for innovation.

By integrating the Yin of Rogers and the Yang of Gadamer, leaders can strive for a balanced, comprehensive approach to innovation that honors both the individual and the collective, the emotional and the rational, the traditional and the novel.

Order and Chaos

Applying the concepts of Order and Chaos to the theories of Hans-Georg Gadamer and Carl Rogers offers a nuanced framework for understanding their relevance in innovation and leadership.

Gadamer as Order

- Tradition and Authority: Gadamer’s emphasis on acknowledging tradition and recognizing authority aligns well with the concept of Order. These aspects suggest a structured, predictable framework for understanding and interpreting situations.

- Structured Interpretation: Gadamer’s hermeneutic circle is a methodical way to interpret texts and situations, suggesting an ordered approach to understanding.

- Rational Discourse: Gadamer’s stress on reflection and dialogue involves the reasoned weighing of various factors, lending itself to a more ordered and systematic approach.

- Historical Context: The importance Gadamer places on historical influences implies that interpretation is not random but grounded in established norms and practices, adding another layer of Order.

Rogers as Chaos

- Personal Growth: Rogers places importance on self-actualization and individual growth, which can be inherently unpredictable and chaotic as individuals explore different facets of themselves.

- Conditional and Unconditional Positive Regard: Rogers’ idea that people can change based on the kinds of positive regard they experience adds an element of variability and Chaos to human behavior.

- Client-Centered Therapy: Rogers’ therapeutic approach is often non-directive, allowing the individual to explore thoughts and feelings freely, which could be seen as embracing Chaos in the quest for self-understanding.

- Inherent Worth of the Individual: By emphasizing the unique experiences of each individual, Rogers invites a level of subjectivity and variability that can be considered chaotic.

Application to Innovation and Leadership

- Ordered Implementation: Gadamer’s perspective can be invaluable when it comes to the structured, systematic implementation of innovative ideas, where Order is often necessary.

- Chaotic Ideation: On the other hand, Rogers’ emphasis on individual creativity and growth can be crucial during the brainstorming and ideation phases of innovation, where Chaos can be beneficial.

- Balanced Innovation: Applying Gadamer’s Order to the organization and validation stages, and Rogers’ Chaos to the ideation and conceptual stages, can result in a balanced and holistic approach to innovation.

- Adaptive Leadership: Leaders can adapt their strategies depending on the phase of the project. They can embrace Chaos for brainstorming and team morale, and Order for execution and alignment with organizational goals.

Understanding that both Order and Chaos have their place in the innovation process can provide a balanced, nuanced approach for leaders. Gadamer’s ordered, rational perspective can help guide decision-making and implementation, while Rogers’ more chaotic, individual-centered approach can inspire creativity and out-of-the-box thinking.

IN THE END

The delicate balance between order and chaos is central to fostering a culture of innovation, particularly in highly structured organizations like the military. While order brings the necessary framework and discipline, chaos is the breeding ground for creative thought and groundbreaking ideas. The theories of Hans-Georg Gadamer and Carl Rogers offer valuable complementary perspectives for navigating this complex

landscape. Gadamer’s hermeneutical principles provide the ordered structure necessary for integrating innovation within existing systems, traditions, and authorities. Rogers, on the other hand, emphasizes the chaotic and unpredictable nature of human creativity and personal growth, which are crucial for the ideation and conceptual stages of innovation.

Applying Gadamer’s focus on order to the organizational aspects of innovation ensures that the new ideas are aligned with the institution’s objectives and established practices. Meanwhile, Rogers’ person-centered theory, embodying the essence of chaos, lends itself well to generating those new ideas and fostering a creative environment.

For leaders striving to champion innovation, understanding and embracing both these elements—order and chaos—can lead to a more nuanced, effective approach. This balanced methodology allows for a dynamic, adaptive leadership style that can successfully navigate the complex terrain of innovation within structured organizations. It is in this creative tension between order and chaos that sustainable, impactful innovation is most likely to emerge.