For some reason, as of late, I’ve been hearing a lot of the theories and principles established by the influential Italian economist and sociologist, Vilfredo Pareto. I knew about the 80/20 principle, but it might need to be explored a bit deeper on how it applies in various aspects of life. In that reading I also came across the concept of Pareto Efficiency, emphasizing its implications in economics and the potential limitations regarding fairness and equality. In addition, I examined Pareto’s theory of the Circulation of Elites, providing historical examples in various contexts, such as the French and Russian Revolutions, Silicon Valley’s technological innovation cycles, and the strategic shifts within the U.S. military. Finally, we considered critiques of Pareto’s theories, highlighting the complexity of societal dynamics beyond Pareto’s models. This conversation reflects the broad influence of Pareto’s theories across multiple disciplines, from economics to sociology, and their continued relevance in understanding contemporary phenomena.

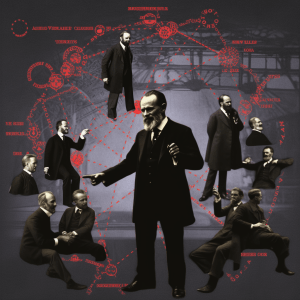

Vilfredo Pareto was an Italian engineer, sociologist, economist, political scientist, and philosopher. He was born on July 15, 1848, and died on August 19, 1923. Pareto is best known for his work in economics and social sciences.

One of his most notable contributions to economics is the Pareto principle, which is also known as the 80/20 rule. The principle states that, for many events, roughly 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. In the context of business, for example, it often happens that 80% of sales come from 20% of clients.

Pareto is also known for developing the concept of Pareto Efficiency or Pareto Optimality, which is a state of allocation of resources in which it is impossible to make any one individual better off without making at least one individual worse off. This concept is widely used in economics, engineering, and other fields to evaluate the efficiency and equity of different allocations of resources.

Additionally, Pareto made contributions to the study of income distribution and formulated what is known as the Pareto distribution, which is a power-law probability distribution that is used in description of social, scientific, geophysical, actuarial, and many other types of observable phenomena.

In sociology and political science, Pareto is known for his theory of the circulation of elites, which posits that in any society, a small number of people (the elites) will hold the majority of power, and that over time different groups of elites will replace each other.

Pareto’s work has had a lasting impact on economics and the social sciences and his ideas are still widely studied and applied in various fields.

80/20 RULE

The 80/20 rule, also known as the Pareto Principle, is a concept introduced by Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto in the late 19th century. The rule is a general observation that most things in life are not distributed evenly.

Pareto originally noticed that approximately 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population. He also observed that 20% of the pea pods in his garden produced approximately 80% of the peas. This led to his formulation of the principle.

This principle has since been applied to a variety of domains. For example:

- Business: Often in business, it’s found that 80% of a company’s profits come from 20% of its customers, or 80% of complaints come from 20% of customers, or 80% of sales come from 20% of products, etc.

- Productivity: Some people find that 80% of their work is accomplished in 20% of the time they spend working, while the remaining 20% of their work takes up 80% of their time.

- Health: It’s often observed in healthcare that 20% of patients use 80% of healthcare resources.

It’s important to note that the 80/20 rule is a heuristic or a rule of thumb, and the actual ratios can vary. The ratio doesn’t have to add up to 100, and it doesn’t always have to be 80/20. It could be 90/10, 70/30, etc. The main takeaway is that outcomes are often not proportional to inputs, with a minority of inputs leading to a majority of results.

Furthermore, the Pareto Principle is not predictive – it can’t tell you which 20% of your effort will lead to 80% of the results. It’s a tool for understanding distribution of effort and results, not a law of nature.

CRITIQUE: Pareto Principle (80/20 Rule): Critics point out that this principle is often treated as a hard-and-fast rule, while it’s more accurately a rough approximation that doesn’t apply universally. It’s seen as an oversimplification that can lead to inaccuracies if followed strictly or without sufficient understanding of the context.

Pareto Efficiency

Pareto efficiency, also known as Pareto optimality, is a concept in economics that measures the efficiency of resource allocation. An allocation of resources is considered Pareto efficient when it’s impossible to make someone better off without making someone else worse off.

In other words, a situation is Pareto efficient if no individuals can be made better off without making other individuals worse off. Every resource is allocated in the most economically efficient manner in this scenario.

Here are a few points to understand about Pareto efficiency:

- Not a Measure of Fairness: Pareto efficiency doesn’t make any claims about the fairness of an outcome. An outcome where one person has everything and everyone else has nothing could still be Pareto efficient, if there’s no way to make others better off without making the one person worse off.

- Maximizing Social Welfare: Pareto efficiency is often associated with maximizing social welfare. A Pareto efficient allocation is not necessarily the “best” allocation from a social perspective, but it’s one where no further “win-win” improvements can be made.

- Use in Welfare Economics: In welfare economics, a discipline of economics that uses microeconomic techniques to evaluate well-being at the aggregate level, Pareto efficiency is an important concept. It helps economists understand what efficiency means and how it can be achieved.

- Relevance to Market Failures: If a market is not Pareto efficient, it’s often due to some type of market failure. These can include things like externalities (where costs or benefits are imposed on people not directly involved in an economic transaction), public goods (which are non-excludable and non-rivalrous), or informational asymmetries (where one party has more or better information than another).

Remember, a Pareto efficient state represents an ideal benchmark of efficiency. In the real world, due to various reasons such as market imperfections and transaction costs, achieving a state of Pareto efficiency is quite challenging.

CRITIQUE: Pareto Efficiency: Critics argue that this concept fails to take into consideration issues of fairness, equality, or moral considerations. An allocation could be Pareto efficient but still extremely unequal or unethical. For instance, a society where one individual has everything while everyone else has nothing could be considered Pareto efficient, which critics argue shows the concept’s insensitivity to issues of fairness or distributive justice.

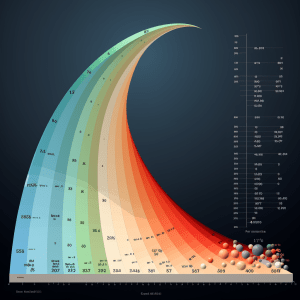

Pareto distribution

The Pareto distribution, named after the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, is a power-law probability distribution used in description of social, scientific, geophysical, actuarial, and many other types of observable phenomena.

The Pareto distribution is often used to represent the distribution of wealth in society, or any other instance where 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes (the Pareto Principle or 80/20 rule). It can also be used to model phenomena with “heavy tails”, such as the sizes of cities, the intensities of earthquakes, and the popularity of books or movies.

Mathematically, the probability density function of a Pareto distribution is:

f(x; k, x_m) = k * (x_m^k) / (x^(k+1)) for x >= x_m, and f(x; k, x_m) = 0 for x < x_m

Here, x_m and k are the parameters of the distribution. x_m is the (necessarily positive) minimum possible value of the random variable, and k is a shape parameter that determines the steepness of the distribution.

Here are a few key properties of the Pareto distribution:

- Scale Invariance: The Pareto distribution is scale invariant, which means if you multiply the variable by a constant, its distribution doesn’t change. This makes it a “fractal” distribution and explains why it’s often observed in nature and society, where patterns tend to repeat at different scales.

- Heavy Tails: The Pareto distribution has “heavy tails”, which means extreme events (far from the median) are more probable than under a “light-tailed” distribution like the normal (Gaussian) distribution. This makes the Pareto distribution useful for modeling phenomena where extreme events are possible and impactful, like financial crashes, natural disasters, or viral posts on the internet.

- Lack of a Mean or Variance: Depending on the value of k, a Pareto-distributed random variable may not have a defined mean (average) or variance (a measure of dispersion). For example, if k <= 1, the mean is not defined, and if k <= 2, the variance is not defined. This can make it challenging to summarize Pareto-distributed data with a single number, and can lead to counterintuitive results.

The Pareto distribution is a powerful tool for modeling a wide variety of phenomena in the world, but like all models, it’s a simplification of reality and doesn’t perfectly capture all the complexities of the data it’s applied to.

CRITQUE:

Pareto’s theory of the circulation of elites

Vilfredo Pareto’s theory of the Circulation of Elites is a sociopolitical theory which asserts that in any society, power is not equally distributed among its members, but rather, it is concentrated in the hands of a small group of people, known as the elite. Pareto argues that this elite will inevitably be replaced over time, but not by a more egalitarian system. Instead, the existing elite will be replaced by a new group of elites in a circulation of political power.

This theory was first presented in his 1901 book, “The Rise and Fall of the Elites”. Pareto believed that elites were split into two types: the ‘governing elite’, who directly influence the direction and rules of a society; and the ‘non-governing elite’, who have the potential to do so due to their superior capabilities or resources, but are not currently in a position of power.

According to Pareto, these elites don’t maintain their power forever. Over time, they will be displaced by members of the non-governing elite in a process Pareto described as the ‘circulation of elites’. This circulation occurs due to a variety of reasons such as complacency, ineptitude, political or economic upheaval, or the ambitious drive of the non-governing elites.

This theory also suggests that it’s nearly impossible for societies to maintain complete equality because power tends to get concentrated in the hands of the few, resulting in a cyclic pattern of power exchange between different elite groups.

It’s important to note that Pareto’s theory of the circulation of elites is not without controversy. Critics argue that it underestimates the power of collective action and social movements, and oversimplifies the complexities of societal power dynamics. Despite these criticisms, the theory remains influential in fields such as sociology, political science, and economics.

CRITIQUE: Theory of the Circulation of Elites: Critics argue that this theory tends to oversimplify complex social and political dynamics. It can be seen as ignoring the influence of collective movements, social reforms, and institutional changes, instead focusing too heavily on individual power dynamics. Critics also mention that this theory can lead to a fatalistic outlook, where change is seen as impossible because any successful revolution merely results in a new elite replacing the old.

HISTORICAL EXAMPLES

The concept of the circulation of elites is a theoretical perspective introduced by Vilfredo Pareto, suggesting that power is always held by a minority group – the elites – and that political and social changes occur when one elite group is replaced by another. Here are a few historical examples that could be interpreted within this framework:

- Fall of the Roman Republic: In the late Roman Republic, the traditional aristocracy was gradually displaced by a new elite of military leaders and popular politicians like Julius Caesar, leading to the establishment of the Roman Empire.

- The French Revolution: The French Revolution saw the overthrow of the long-standing monarchy, which was the elite of the time, and its replacement with a revolutionary elite. Later, power was concentrated in the hands of Napoleon Bonaparte, demonstrating a shift in elite power from monarchy to revolutionary leaders to a military dictator.

- The Russian Revolution: The Russian Revolution of 1917 resulted in the overthrow of the Russian Tsar Nicholas II and the aristocracy. Power was taken over by the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, representing a shift from a royal elite to a communist elite.

- Chinese Communist Revolution: The Chinese Communist Revolution culminated in 1949 with the Communist Party, led by Mao Zedong, displacing the incumbent Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) as the ruling elite.

- Transition of British Rule in India: India’s independence from British rule in 1947 led to the transfer of power from the British elite to the Indian National Congress, a largely western-educated Indian elite.

- Modern Democracies: In modern democratic systems, there is a regular circulation of elites due to elections. Different political parties, each with their own elites, gain power at different times.

Remember, the concept of the circulation of elites doesn’t suggest that societal change is always good or bad, but rather, it focuses on understanding the dynamics of power and how that power shifts over time.

SILICON VALLEY: CONTEXT

Silicon Valley, located in the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area in California, has been known as a major hub for high tech innovation and development. The “elites” in Silicon Valley typically refer to successful entrepreneurs, top executives, and venture capitalists. The “circulation of elites” can be seen in several ways in this context:

- Shift from Hardware to Software and Internet Companies: During the early years of Silicon Valley, the dominant firms were hardware manufacturers like Hewlett-Packard and Intel. These companies formed the original elite. Over time, as the technology industry evolved, there was a shift towards software and internet-based companies. Companies like Google, Facebook, and later Uber and Airbnb, led by a new breed of entrepreneurs and executives, became the new elites.

- Rise of New Companies and Leaders: Even within the software and internet space, there has been a circulation of elites. Older firms like Yahoo and AOL have declined, and their executives have been replaced by leaders from newer companies like Twitter, Snap, and more.

- Venture Capital Influence: Venture capitalists (VCs) are also a significant part of the Silicon Valley elite. The influence and dominance of certain VC firms can change over time. For example, while firms like Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins were once the most influential, newer firms like Andreessen Horowitz have emerged and become part of the elite.

- Change Driven by Innovation: The circulation of elites in Silicon Valley is heavily driven by innovation and the continuous emergence of new technologies. From personal computers to the internet, mobile technologies, artificial intelligence, and now blockchain and cryptocurrency technologies, the leaders at the forefront of these emerging technologies often become the new elites.

So, in Silicon Valley, the concept of the circulation of elites is quite dynamic and tied closely to the rapid pace of innovation and the emergence of new tech trends. As new technologies rise and fall, so do the elites who lead and fund those trends.

SILICON VALLEY: EXAMPLES

The landscape of Silicon Valley has changed significantly over the decades, with different technology companies and leaders rising and falling in prominence. This can be seen as an example of Vilfredo Pareto’s “circulation of elites,” with power shifting between different groups over time. Here are a few examples:

- 1970s – Early Microcomputer Revolution: In the early days of Silicon Valley, companies like Hewlett-Packard and Fairchild Semiconductor were dominant. They were the ‘elites’ of that time, pioneering new technologies and driving the growth of the valley.

- 1980s – Rise of Personal Computing: This period saw the rise of companies like Apple and Microsoft (although based in Washington state, it played a significant role in the technology landscape). The elite shifted from hardware semiconductor companies to those focused on personal computing. Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and their teams rose to elite status, driving innovation and setting new technology trends.

- 1990s – Dot-Com Boom: The late ’90s saw the dot-com boom, with new internet-based companies becoming the elite. Companies like Netscape, Yahoo, and later Google, led by figures such as Marc Andreessen, Jerry Yang, and Larry Page, redefined the technology landscape.

- 2000s – Emergence of Social Media and Mobile Computing: This period saw the rise of companies like Facebook and Twitter, and the resurgence of Apple with its iPhone, marking a shift in elite power towards social media and mobile technology. Figures like Mark Zuckerberg, Jack Dorsey, and a revitalized Steve Jobs, became the new elites.

- 2010s – Focus on AI and Emerging Technologies: The mid-to-late 2010s saw the rise of AI and machine learning, with companies like Tesla (and its charismatic CEO Elon Musk) and Alphabet’s DeepMind at the forefront. The ‘elite’ began to include companies and leaders focusing on these transformative technologies.

This cycle of rise and fall, or the circulation of elites, in Silicon Valley illustrates how the power and influence of certain companies and individuals waxes and wanes in line with technological innovation and market trends.

US MILITARY: CONTEXT

In the context of the US military, the “elites” typically refer to the high-ranking officials and leaders who make critical decisions that impact the country’s defense policy and military strategies. Here, the concept of the “circulation of elites” can be understood as the rotation or turnover of these leaders over time due to various factors.

The circulation of elites can be seen in several ways in the US military:

- Career Advancement and Retirement: Military leaders usually ascend the ranks over time, with the most senior positions often held by individuals with decades of service. However, military service often has mandatory retirement ages or years of service caps, which ensures a steady rotation of individuals in top leadership positions. For example, a four-star general must retire after 40 years of service or after four years as a general, unless they are appointed as the Chief of Staff of the Army or Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

- Change of Administrations: The President of the United States, as the Commander-in-Chief, can appoint and dismiss top military leaders. Therefore, when administrations change, it can result in changes to the military elite, especially in top civilian positions like the Secretary of Defense.

- Strategic Shifts: The focus of the US military has shifted several times throughout its history, such as from focusing on state actors during the Cold War to non-state actors and counterinsurgency in the post-9/11 era. These strategic shifts can lead to changes in military elites, as different skill sets and types of experience become more relevant.

It’s worth noting that the concept of the “circulation of elites” in the military is quite structured and regulated compared to other contexts due to the nature of the military hierarchy and the regulations governing promotions and appointments. Still, shifts in leadership and strategic priorities can and do result in changes among the top military brass.

US MILITARY : EXAMPLES

Historically, there have been significant shifts in the leadership or ‘elite’ within the US military. These shifts are often prompted by external circumstances, such as changing political administrations, major conflicts, or the evolution of military tactics and technology. Here are a few examples:

- World War II: Prior to World War II, the US military was not a major force on the global stage. The necessities of the war saw a significant shift in the elite as leaders who could handle large-scale mechanized warfare, such as Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower and George Patton, rose to prominence.

- Post-World War II/Cold War Era: After World War II, with the onset of the Cold War, the nature of the military elite changed again. With the advent of nuclear weapons, strategists and diplomats often held sway. Figures such as General Curtis LeMay, known for his role in strategic bombing during World War II and his later advocacy for a strong nuclear deterrent during the Cold War, were indicative of this shift.

- Vietnam War Era: The challenges of the Vietnam War, a conflict characterized by guerilla warfare and complex political considerations, led to another circulation of elites. General Creighton Abrams, for example, replaced General William Westmoreland as the U.S. commander in Vietnam in 1968 and shifted the U.S. strategy away from large-scale operations and more towards pacification and “winning the hearts and minds” of the Vietnamese people.

- Post 9/11 Era: The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan required a different type of warfare and leadership again, bringing counterinsurgency to the forefront. Leaders such as General David Petraeus, who helped develop and implement a new counterinsurgency strategy in Iraq, rose to prominence.

In each case, changes in the nature of warfare, geopolitical considerations, and shifts in national strategy brought different military leaders to the forefront, demonstrating a kind of “circulation of elites” within the U.S. military structure.

IN THE END

Vilfredo Pareto’s theories offer some interesting insights into a wide range of social, economic, and technological phenomena. From understanding the distribution of resources with the 80/20 rule, evaluating optimal efficiency in economic transactions, to analyzing shifts in power with the Circulation of Elites theory, Pareto’s contributions provide valuable frameworks for analyzing complex systems. However, it’s important to keep in mind that his theories, like all models, are simplifications of reality, and should be complemented with other perspectives to gain a comprehensive understanding.

Navigating the evolving landscapes of society and technology, it’s now more important than ever to critically engage with these theories and their implications. Whether a business leader seeking to optimize an organization, a technologist innovating in the heart of Silicon Valley, or an individual trying to make sense of global socio-economic dynamics, Pareto’s principles can offer insights.